The Sunday Mail

I BELIEVE that any conversation related to the Zimbabwean dollar – be it its banishment or second coming – must have a modicum of pragmatism, realism or any other “ism” that puts across a compelling and forceful argument for it to be generally acceptable.

From what I have observed, conversations on the Zimbabwean dollar are generally emotive and often degenerate into unnecessary name-calling and mudslinging.

Government’s pronouncement on this issue, as spelt out in Zim Asset, is unequivocal: the multi-currency system, to which the Indian rupee and the Chinese yuan was recently added, will anchor the country’s economic development initiatives to 2018.

But many agree that the country has to begin to set the benchmarks and foundations crucially needed to re-introduce a local unit of exchange.

As a result, debate must be centred on defining the benchmarks and foundations, and anything else is irrelevant.

It is for this reason that I strongly believe that Clemence Machadu’s article published in The Sunday Mail issue of 25-31 May 2014, which sought to re-ignite debate on resurrecting the local currency, was not only way off the mark but dangerous as well. In my opinion, his views were not matter of fact but highly emotional; his piece didn’t quite validate his strong views.

“Who said talking about the local currency should be a sacred preserve of those who have read economics textbooks, written by foreigners inspired by their peculiar contexts?

“Those who are familiar with the Washington Consensus and why ESAP did not work will sympathise with me. Textbook economists stood approvingly behind ESAP. It failed.

“Textbook economists will talk about weak terms of trade and all the jibber-jabber about fundamentals not being yet ideal, as if there is a bell that shall ring to announce that,” submitted Mr Machadu’s in his piece.

Well, talking about “economic textbooks” written by “foreigners” and describing economists’ assertions on the country’s weak terms of trade as “jibber-jabber” will not quite endear one’s views to those willing to engage in a serious intellectual debate.

The insinuations and innuendo put through such type of remarks are similar to some of the controversial views that are being forcefully made by our radical brothers in West Africa.

Not everything foreign – or Western – is bad.

Deng Xiaoping, the Chinese reformist leader who is believed to have ushered China into a successful market economy, said in 1961, “I don’t care if it’s a white cat or a black cat. It’s a good cat as long as it catches mice.”

This is being pragmatic.

But this brief is not meant to attack Mr Machadu’s views but to interrogate some of the simplifying assumptions he made which I believe betray our past experiences and circumstances.

There were two critical issues that were raised: Firstly, it is assumed that a currency of Zimbabwe can easily be “protected” and “manipulated” to create balanced and sustainable economic growth.

Also, it is assumed that the “tight” liquidity conditions are being caused by the US sanctions targeted at local assets.

Granted, the re-introduction of the local currency will naturally capacitate the Reserve Bank of Zimbabwe by making available monetary tools that can be used to intervene in the market.

Economists argue that it is easy for a central bank to either tighten or ease monetary policy in order to create the amount of money circulating in the economy.

Being able to control money supply growth can enable authorities to either pump in more cash as demanded by the market or mop up excess liquidity that might be inflationary.

But how can the Reserve Bank, which currently does not have any reserves – except for gold coins only valued at US$501 309 – be able to anchor the local unit or defend it?

Usually, central banks use their foreign currency holdings to determine the value of their local currencies. Without any reserves to back it, a local currency is likely to be susceptible to the vagaries of the market, rising and falling according to the whims of the market.

In such circumstances, monetary authorities will most likely lose control. There is empirical evidence to prove this.

In the period between 2003 and 2006, as the sanctions imposed by the United States of America and the European Union bloc began to take their toll on the economy, the country’s ability to generate foreign currency from the productive sectors was naturally affected.

Zimbabwe had to rely on exports, particularly gold, and free funds in order to meet its import requirements.

It was not surprising therefore that in the four-year period global foreign currency receipts amounted to US$5,8 billion, with gold accounting for 72,9 percent of the figure.

Free funds and Money Transfers Agencies contributed US$1 billion of the amount.

It is no secret that the RBZ had to lean more and more on exporters and other holders of free funds such as non-governmental organisations to fund the country’s critical imports – food, fuel and essential drugs.

The scramble for foreign currency in a very tight market led to discord on the interest rate market, including in valuing the Zimbabwean dollar.

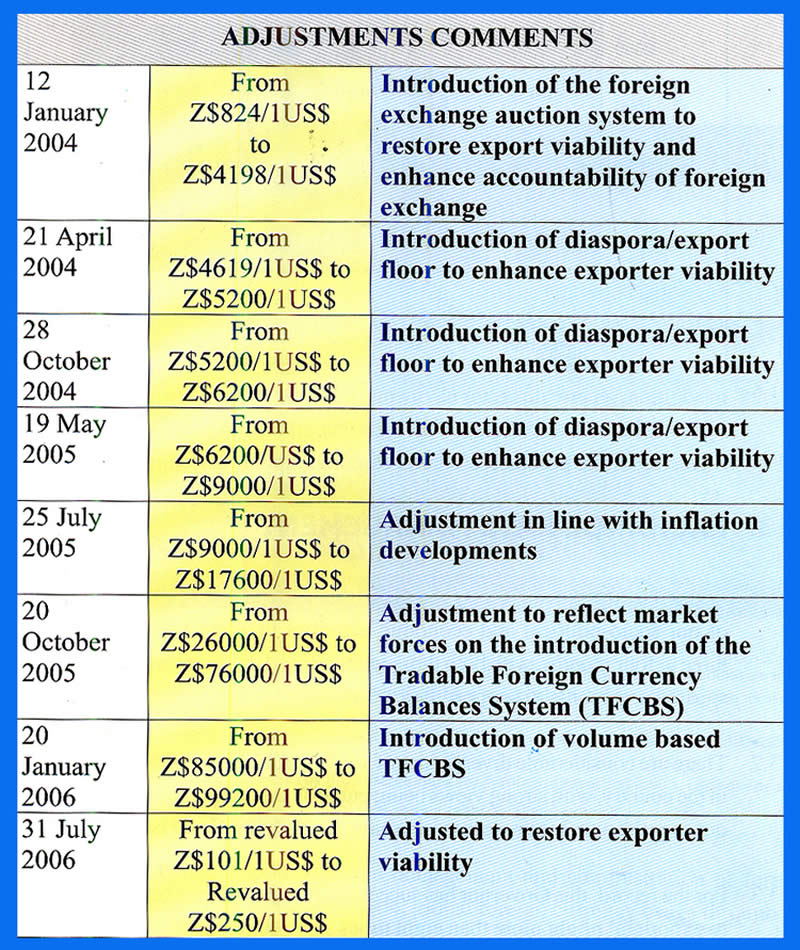

This is why between January 12 2004 and July 31 2006, the central bank had devalued the local unit more than eight times.

“It is clear that the foreign exchange market setbacks are a supply and demand issue, linked to sanctions against the country, linked to lack of balance of payments support, linked to smuggling and indiscipline in the economy, linked to shortage of funds to support whatever devaluation we may contemplate, and above all, linked to the poor performance of the export sectors . . .

“So, we ask ourselves, what then do you want the Governor to do? Continue to devalue and bless the parallel market? If so, devalue to what level?” the then RBZ Governor Dr Gideon Gono said in the 2006 year-end Monetary Policy Statement.

Faced with increased desperation to meet Government’s critical demands, the RBZ had to turn to the printing press and raid companies’ foreign currency accounts as a last resort.

The apex bank currently owes gold miners – Caledonia, Metallon Gold, Falcon Gold, Rio Zim and Mwana Africa’s Freda Rebecca – more than US$20 million. The debt, however, has since been transformed into Special Tradeable Gold-backed Foreign Exchange Bonds.

Also, pumping paper money – whose value did not have any backing – into the system led to worthless paper chasing high value goods and services.

Retailers could not easily restock because of bottlenecks that were experienced in accessing foreign currency through the formal channels.

Shortages naturally resulted.

To this day the prospect of the RBZ behind the printing press is enough to spook even the strong-hearted in our midst.

If we could not defend our local unit then, what makes us confident that we can defend it now, especially when our vaults remain empty?

It is also folly to assert that the current cash shortages, which have been loosely referred to as tight liquidity conditions, have been a feature of the dollarised environment.

Foreign currency shortages pre-date the multi-currency system, and this is why economists blame our weak terms of trade.

If anything, money supply growth has been improving after the multi-currency system.

Statistics from the Zimbabwe Revenue Authority show that while the country only managed to generate US$988 million in revenues in 2009, collections grew to US$2,2 billion in 2010.

By the end of 2013, the taxman had racked in more than US$3,4 billion. Similarly, deposits in the banking sector have been trekking northwards. In the six months to December 2013, the banking sector attracted more than US$89 million in new money, driving total bank deposits to US$4,73 billion.

So, what worsening conditions are we talking about?

It is logical: Zimbabwe is consuming more than it is producing. In the first three months of this year, the country had imported more than US$1,4 billion worth of goods, but exports in the same period had dropped to US$625 million, yielding a trade gap of US$775 million.

South Africa has become a huge cash till for Zimbabwe and we are literally exporting our cash.

We should therefore not be surprised with the obtaining liquidity challenges. Obviously we cannot compare ourselves with China, which has a US$3 trillion cash stockpile to defend the yuan.

Just last week, Zambia’s kwacha fell to record lows as mining companies withheld foreign currency, creating shortages in the market.

As I said before, any useful argument on the local currency has to talk about the benchmarks needed to begin the process of re-introducing the dollar.

Happily, Treasury had indicated it will begin building reserves in the form of both gold and platinum.

But we need to ascertain what quantity would be sufficient for conditions to be ideal for the Zimbabwean dollar.

Some economists say a standard three months import cover – roughly more than US$1,5 billion using the current rates – is standard. Also the productive sectors of the economy need to be developed.

But, most crucially, there must be a “spider web”, where money is spent locally and is encouraged to circulate within the local eco-system.

A policy bias towards local procurement could significantly help. Experts have to thrash out all these nitty-gritties.

At the end of the day, our collective arguments should be used to create the template necessary to guide policymakers to draft a white paper on how the Zimbabwean dollar will return.

We do not need to be emotional about this, we only need to be rational.