The Sunday Mail

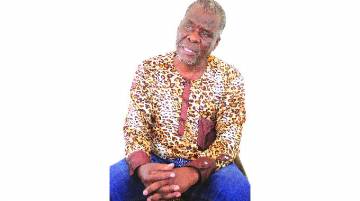

Cde Andrew Ndlovu was christened Volunteer by the Soviets when he went to Ukraine for military training. In this, a continuing conversation with GARIKAI MAZARA, he narrates his return to Rhodesia, three years after leaving the country, to face the enemy.

*********

Q: So what happened when you got to Nairobi?

A: To our surprise, when we arrived at Nairobi airport, no black person attended to us but only Soviets and we were taken to the President Hotel. Our security at the hotel were Soviets; they were all over the streets. The following day we boarded Aeroflot to the Ukraine, to one of the biggest military academies in the Soviet Union then. This is where most of our military leaders trained — Dumiso Dabengwa, Samora Machel, whoever, they went there.

We were now divided into groups, each group specialising in different aspects of warfare. I was to specialise as a field commander and my scope included driving, engineering, anti-air, small artillery pieces, katyushas, MS7. We covered a lot up to brigade level.

In 1977, around June, Joshua Nkomo came to address us as we were preparing to complete our training. It was more or less a diploma in military science in the sense that the level of training in those six months was intensive.

When we arrived back in Lusaka, there was an American President who was scheduled to land at about the same time and we had to fly around until he landed. We were the first to bring Aeroflot to Lusaka, if not Southern Africa. And because of the snow in the Ukraine, we were now almost white.

Q: What was the language of instruction in Ukraine? Was it English, Russian?

A: Our instructors were most (of the soldiers) who fought the Second World War. They were well-experienced and spoke Russian and there were interpreters. Those guys don’t like speaking other people’s languages. In Zambia, we were then taken to FC (Freedom Camp) where we found between 300 and 400 recruits and we were asked to train them.

Then Nikita Mangena came and addressed us, that some of us were going to be instructors and some were to go home and be commanders. As young people, we wanted to fight.

We were told there was going to be a parade where instructors and commanders were to be selected, so we ran away so that when we came back that selection would have been done. They called two or three parades to select instructors to the ZPRA camps. The reason why I didn’t want to be an instructor is that I hated running and the toyi-toying.

Q: When you went to Freedom Camp, was this before or after the attack? The Rhodesian attack?

A: It was before. This was around June and that attack must have been around October of that same year, 1977. Now they didn’t tell us the date when we were going to the front, so we went to an area called Kabanana and sold our Soviet watches so we could drink. When we came back in the night, we found our colleagues who had been with us in the Soviet Union gone to the front. Mazinyane, he was our intelligence guy, asked us where we had gone to and we told him we had taken a night out.

Q: When we travelled to Freedom Camp the other year, we came across some children, could be slightly over 20, who were born of ZPRA comrades . . . could you have left yours there?

A: (laughs). Those could have been born in my absence. But that could happen because guerrillas could go into the villages, especially the trained ones, not the recruits, because no one would control the trained ones that much. We knew our duties. Some would go out and buy mbanje because at that age we believed mbanje could make you brave; that in the case that when you die fighting you don’t know how you would have died.

So Mazinyane was not amused that we had gone out while others had been deployed, so we were detained in a small guard-room. We were released later and sent to the kitchen, to help the recruits cook. But we didn’t cook at all, we were just enjoying the food there. Then Ambrose Mutinhiri and Ananias Gwenzi (Valerio Sibanda) came and said, “get ready guys”. We were now three and they drove us in their Land Rover to Choma, just towards the Rhodesian border.

In the morning, a Jeep came to take us to the base GC1, Guerrilla Camp 1, emagojeni. We called it emagojeni because of the mountains. Lemon was the camp commander and Mike was in charge of security. We deployed the ZEGU anti-air guns up the mountains, the medium machine guns down, with the kitchen along the river where there was plenty of water and thickets, so that no-one would see our smoke as we cooked. I stayed there for a month, then I was advised to lead a team . . .

Q: We are now in 1970 what ?

A: 1977. It was during between July and August. At GC1 we had some joint operations with the Zambians because the Rhodesians had infiltrated Zambia. During one operation, the Zambians had their truck blown up by the Rhodesians in an ambush on their way back.

Then I was tasked to lead a reconnaissance team to Lake Kariba so that we could monitor what was happening in the lake. The Rhodesians would bomb the islands, trying to destabilise the routes to and from Zambia. We were a small group, six or seven. ZPRA would use the islands to cross into and out of Zambia. It was the same year that Lord Malvern, a cruise boat, that used to carry whites from Kariba to Livingstone, was hit by ZPRAs.

Since we had interest in fighting, not reconnaissance, we defied the instructions that we had been given. We would fight with the Rhodesians at night because we wanted to fight. We would bomb different islands with anti-tank grenades.

Q: Approximately, for how long did you operate in the lake?

A: Around December, we received a signal from Lemon, who was at GC1, instructing us to get back to the mountains. There we found Jevan Maseko, war name Enock Tshangane, who told us that we were now going to the front. He asked us to leave the AKs which we were using. We left for DK, a ZPRA crossing point on the Zambezi River, “death or casualty”, that is what DK stood for. We found some guys that we knew and there was a unit there, under someone’s command. Myself and George Malalaphansi were to join that unit, but as overall commanders, to assist in the command of the unit and ensure that the war was executed according to plan.

It was my first time to come across such slippery terrain, made worse by us carrying heavy artillery such as bazookas, katyushas, mortar 60s, mortar 82. Looking down at the river from up there, the Zambezi looked very small but on reaching it, it was very wide.

Q: On average, how many kg of artillery would one person be carrying?

A: On average each person had a Gun 75, a B10, Mortar 82 and Mortar 60. That is heavy artillery. At one point we were so tired we had to steal some donkeys we found in the bush to help us carry the ammunition up to the Zambezi River. We arrived at the river bank by 6pm and waited until it was dark. There were some small boats for Rhodesians that would patrol the area but we managed to cross, the 140 of us. We were a semi-regular mechanised guerrilla unit, whose mission was to hit garrisons.

The following morning, we moved to Makulubusi, Binga. We moved through a dry area, more like a desert, and we had our lunch in the desert, washed down with some tea and biscuits.

Q: You were well supplied in terms of food and weapons?

A: ZPRA, we had more than enough. It is us who were supplying Zanla guys because Zanla guys didn’t have enough modern weapons. That is why we were able to hit and bring down those Rhodesian planes. We had medium machine guns, RPK, LMG, bazookas, anti-personnel, grenade launchers, just to mention a few. These are weapons that, when you engaged the enemy, it would feel they have met their match. We were a good match for the Rhodesians. Even at our age, in the early 20s, you can imagine no wife, no children, no responsibility and the AK was my wife. We enjoyed that life, the bush life.

We arrived at Makulubusi around midnight, having started the journey around 5am. We were well received by the locals, who prepared food for us. Around 3am, we left for Lupane, until we got to the Hwange highway. We arrived at Tinde around 2pm and we rested. Just as the villagers were preparing food for us, helicopters came above us.

A fight ensued and we hit one helicopter which made a forced retreat. Our instincts told us that there had to be a ground force following us and we started firing in the direction that we had come. Whether the enemy was 200 or 300 metres from us, we did not care as we knew that the effective range of an AK was about 800m, and it could kill anyone within that range.

After some fighting, we had to retreat and moved towards Lupane. We arrived at Dongamuzi and it became our area of operation. We had to split our unit into smaller units. We familiarised ourselves with the terrain and the people.

It was in the same year, 1978, when the Rhodesians started Operation Tangent, where they planned to cut off the supply line, to hit the guerrilla bases from the rear. This operation was supported by more than 10 helicopters. By this time, we had put on a full war jacket.

And in February, we received a lot of rainfall, and we would walk and sleep in our boots such that our feet were white. But we fought all the same. At some point, there were battalions of mercenaries, some who had fought in the Second World War but we engaged them all the same.

Most of our encounters were spontaneous attacks, which we had not prepared for. When you fired, it was not because you were fighting but you would fire just to diffuse the enemy then retreat. That is guerrilla warfare.

In one of engagements, one of our guys, Lenny, was captured by the Rhodies but he was never killed, and was released during ceasefire. He is still alive, though I am not sure where he could be now.

In the next instalment, Andrew Ndlovu talks of an operation where he was hit by a bullet and lost 14 teeth, a split tongue, but managed to walk away with his life. Make a point not to miss it . . .