The Sunday Mail

Dr Christine Peta

The focus of this article is on the link between deafness and mental health. Research has indicated that about 15-26 percent of the world’s population is deaf, and most deaf people live in developing countries including in Zimbabwe. About a quarter of deaf people have a high chance of having additional disabilities that include blindness and mental health problems.

Vision loss among persons who are also deaf may be caused by the fact that a number of inherited disorders often cause a double sensory loss, for example the Usher syndrome is one of the typical examples of an inherited disorder that causes a person to become deaf as well as to lose his or her sight. In simple terms, a syndrome is a disease or disorder that has more than one feature or symptom. However, the focus of this article is to highlight the reasons why deafness may progress to mental disorders.

Some mental health problems that arise among deaf children are caused by the fact that parents often delay in assisting deaf children to develop language and effective ways of communicating with family members and peers. The belief that there is nothing that parents or guardians can do when a child is born with deafness or when the child later becomes deaf is wrong.

A recent study carried out by Dammeyer and Chapman (2017) revealed that a deaf child who is able to take part in communication with others at an early stage of his or her life, has a lower chance of acquiring mental health problems. Effective communication through either speech or sign language has a lot to do with whether a child will develop mental health problems or not. Delays in the development of language that usually stem from hearing loss often cause a number of challenges in the developmental journey of the child and such challenges may include emotional behaviour disorders.

The family environment plays a critical role in contributing towards the development of language of a deaf child. When deaf children are misunderstood within their own families, they become stressed and frustrated, resulting in a higher likelihood of developing mental disorders, compared to deaf children who effectively communicate with their family members from an early age.

Emotional attachment of parents and sensitivity of caregivers has a positive impact on the mental health of children; parents should bear in mind that increased levels of stress within families because a child has been diagnosed as deaf has a negative impact on the mental health of the child. Parents who are less stressed, stand a better chance of raising a deaf child who has nil or less mental health problems.

Nevertheless, deafness and its associated impact does not come in clear cut obvious ways, but the common mental health problems that occur among affected deaf persons are; aggression, depression, oppositional defiant disorder, conduct disorder, insomnia, anxiety, and delinquency.

Some deaf children may also show signs of hyperactivity and those who have low intelligence levels may also have attention disorders. Although research has indicated that there is a high prevalence of mental problems among deaf or hard of hearing persons, the extent of hearing loss that results in mental disorders has not yet been established.

Some scholars have buttressed the importance of taking children for early hearing screening before the children attain the age of one month (Williams, 2017). If it is confirmed at this early age that a child has a hearing loss, parents should seek an intervention program for the child, before he or she reaches the age of six months. Some studies have recommended cochlear implantation and argued that such implantation enhances the mental health of many deaf children.

Parents or guardians should therefore not sit back and watch their children grow without assisting them to develop any kind of language. Such an approach in part increases the chances of acquiring additional disabilities, which in some instances may be of a psychiatric nature. How can a deaf child who does not have any way of communicating with his or her family or community, be able to maintain his or her sanity in a hearing society which creates communication barriers for him or her?

However, communication methods should not just be limited to sign language, but assistive devices such as hearing aids should also be considered, as well as lip reading, writing and the use of visual aids such as photos and drawings.

Nevertheless, complete reliance on lip reading or note writing is not advisable; the risk is that people who read lips may not understand the full discussion and they may resort to using guess work to complete the gaps, leading to gross communication errors.

A dependency on note writing alone is also not appropriate considering that deaf persons are likely to have poor writing skills because they start school much later on and in most instances they have lower levels of education.

To illuminate such challenges, De Wet (n.d.) presents an example of a piece written by a deaf person: “I know write. I know a-little. Teacher write, talk, talk, write, talk. I fed up. Woman talk, talk, I write. Push down hand. Talk I know nothing. Talk negative only. I write intelligent no. Only write word. Sentence no. Words. Know word few. Sentence I not make.”

When communicating with a deaf person particularly in healthcare and rehabilitation settings, it is important to check understanding by maybe politely asking the person to repeat what may have been discussed. Otherwise a lack of effective communication may increase the progression of mental health challenges when deaf persons feel that they are not being taken seriously or that they are being misunderstood.

Stigma and discrimination may also cause deaf persons to be depressed, irritable anxious, to experience insomnia and to feel inferior.

In addition, societal gender role expectations may cause some deaf men to acquire mental disorders due to difficulties they confront in seeking to attain bread-winner status, because of limited educational and employment opportunities that are common among persons with disability.

Deaf persons also require improved access to health and mental healthcare provided through specialists who are trained to communicate directly with deaf persons or through sign language interpreters. However, most healthcare staff are unable to use sign language; as a result deaf persons are commonly marginalised in clinic and hospital settings, making it hard for them to access healthcare, thereby increasing their chances of acquiring mental health problems.

According to Fellinger et al (2012) the mental health examination of deaf persons should ideally be conducted by a specialist who uses sign language. However, it is not uncommon to find medical records that are written “A proper diagnosis could not be established because the person could not talk” or “the person was not examined or treated because she could not talk.” Such an approach represents a serious violation of the right of deaf persons to access health care, a practice which is embedded with the risk that deafness may progress to mental disorders.

Way forward

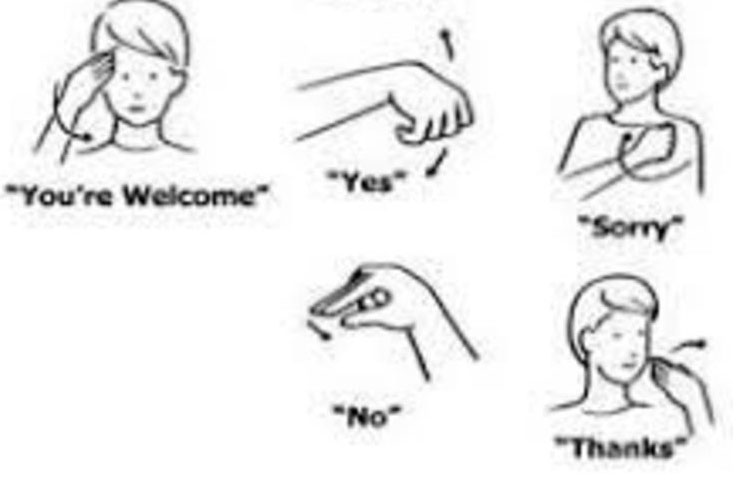

Both the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disability (2008) and the Constitution of Zimbabwe (2013) uphold the use of alternative modes of communication by persons with disability including sign language. We should all make an effort to learn to use sign language within our families and communities, that way we contribute towards preventing the progression of deafness to mental disorders.

Dr Christine Peta is a public health care practitioner who, among other qualifications, holds a PhD in Disability Studies. Be part of international debate on how best to nurture a society which is more accessible, supportive and inclusive of disabled people. Partner with Disability Centre for Africa (DCFA) on e-mail [email protected]