The Sunday Mail

Munyaradzi Huni

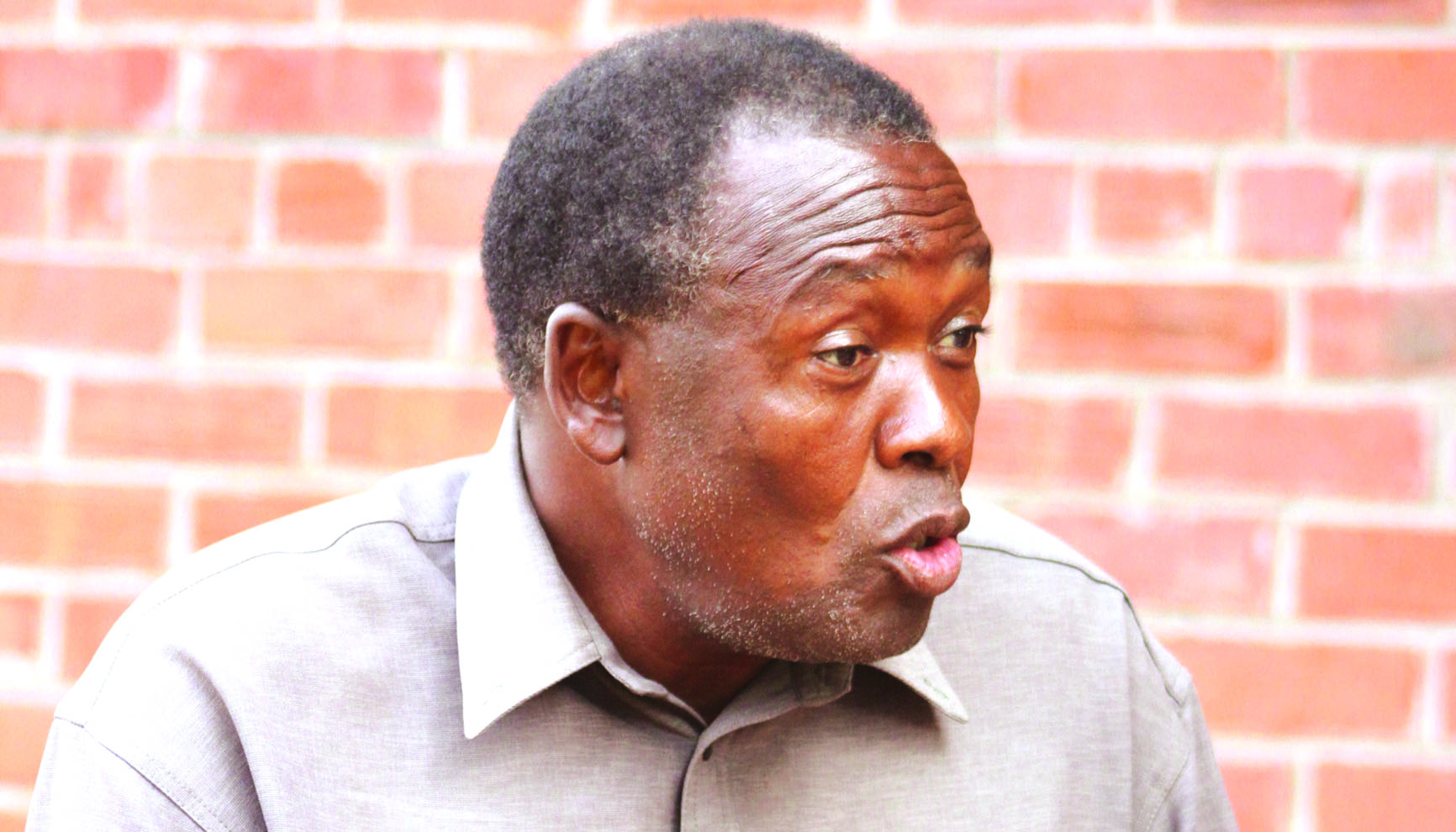

One by one, they are going. And now they seem to be going at a worrying pace. Shamwari dzeropa! A few months ago, I wrote a piece saying adiós to Mudhara Vhuu together with Cde Edzai Chimonyo. Now it is Comrade Wereki Sandiyani, the fearless gandanga from Dotito, whose Chimurenga name was Cde Phillimon Gabela. Slowly, I am dying with these comrades.

Some called him Phillip.

I am not sure if those I have spoken to understand me when I say “you can’t remain the same after talking to these former freedom fighters”. Their stories don’t just recruit you to become an unwavering patriot. For lack of a better expression, let me say their horror stories “cook you” and “stew you” such that you become embedded in their pain and anguish.

From 2012 up to 2018, I interviewed over 140 former freedom fighters from the country’s liberation war. They told me gruesome stories, some too gory that they sounded like those stranger-than-fiction stories. At times the narratives were too horrific that I would doubt their authenticity. To cross-check facts and establish the authenticity of some of the stories, I would ask probing questions from different angles.

However, there was one interview where I didn’t need to ask the probing questions. The evidence of the horror was clearly visible. Throughout the interview, I kept asking God why He could let one man to go through such a horrendous experience. My heart was bleeding, but to my utter surprise, Cde Gabela spoke about the torturous ordeal that he went through at the hands of Ian Smith’s cold-blooded soldiers, as if this was just another sad story from the Second Chimurenga.

To show that this was not just any other ordinary narrative from the liberation struggle, The Sunday Mail June 2-8, 2013 edition published a story headlined “A chilling conversation with a “dead man”. Right at the top of Page 11, I wrote a small note saying: “WARNING: This is not for the faint-hearted. Those of a nervous disposition are advised to read with extreme caution. Cde Wereki Sandiyani from Dotito, whose Chimurenga name was Cde Phillimon Gabela, is a real gandanga and he uses raw language to hammer his points home.”

In the interview, Cde Gabela told me how he joined the liberation struggle on January 1, 1973 together with about 235 other recruits. He narrated how when they got to Teresera Base, where there were about 3 000 recruits, they were attacked by Rhodesian air force, leading to the deaths of many recruits. Some of the ZANLA commanders at that base included Cdes James Bond and Chemist Ncube.

“There were around 60 armed comrades and they fought back but the bombardment was just too heavy. Death and blood was smelling all over. I think over 1 000 recruits died that day,” he recalled.

After this attack, Cde Gabela was sent back into Rhodesia. He operated at the war front for a whole year before receiving military training.

During that year, he was involved in countless battles being led by commanders such as Cdes David Zvinotapira and Clever Zviroto Mabhonzo.

He went for military training at Mgagao Base in Tanzania in 1974 where some of his instructors included Cdes Kenneth Gwindingwi, Misihairabwi, Tendai Pfepferere and Dzinashe Machingura.

The training took about six months and he was part of the group that was sent to capture the leaders of the Nhari-Badza Rebellion.

He narrated how as the commander of about 160 comrades, he “broke the rules” as they went to attack Rhodesian forces who had camped at Katsukunya School in Mutoko.

“Around 1pm, we started walking towards the mountains, but under the cover of huge trees. As commander, I was right in front of the procession so that I could command my soldiers in case of a battle.

“After walking for some distance in this valley, one of the comrades who was third from me in the procession said: ‘shef, honai makudo ayo?’ I didn’t pay much attention to him, but we later discovered that he had not seen baboons, but they were actually Rhodesian soldiers who were crawling and retreating trying to find a vantage point to attack us.

“I think we were now in their killing bag. I just heard a gunshot. We quickly took cover. I looked back and saw that the comrade who had said he was seeing baboons had been hit. While under cover, we saw him rolling his eyes and dying. Then suddenly there was a heavy exchange of gun fire with the enemy forces. After a few minutes, part of the valley was on fire. In about 15 minutes, the battle was over. We only lost one comrade while Cde Blackson Chachaya got injured,” said Cde Gabela.

He said after that battle, the Rhodesian forces retreated, but came back again around 2pm for another fierce battle.

“That is when I was shot on the ankle joint while lying in cover. The ankle joint was shattered to pieces. We fought back. I didn’t realise how bad my wound was until I tried to stand up and run. My comrades proceeded with the journey, but I couldn’t walk. I remained behind hiding.

“One of the comrades, Forbes Nyathi, came back after realising that I had been injured. He came back and said: ‘Comrade, ndipei pfuti.’ At first I refused because I was thinking I wanted to protect myself, but mutemo wehondo was that once you got injured and you couldn’t continue with the war, you were supposed to throw your gun to the next comrade so that he or she picks it up and goes with it. The other thing was that once you saw that you couldn’t make it out of a battle, you were supposed to kill yourself,” he said in true gandanga style.

To capture the horror that followed, below are excerpts from the interview.

***************

MH: So this comrade came back to take your gun because he didn’t want you to shoot yourself?

WS: Yes! I didn’t kill myself because this comrade came back too fast and asked me to give him my AK47 together with my pistol. He even tried to carry me, but I refused because he would also be shot and killed. I said: ‘Chiendai comrade. Pamberi nehondo!’ This comrade left me behind. After a while, I saw four helicopters flying above and in no time I heard gunfire in the direction that the comrades had gone. I was now thinking about the safety of my fellow comrades. As the gunfire continued, I could hear that one of the helicopters had been gunned down. That made me feel good.

I remained in that hiding place for a while thinking of my next move. I started hobbling, slowly trying to go back to the village we had came from. I was pulling a tree branch to erase my footprints so that the enemy forces could not track me. After a while, I rested under a big rock assessing my leg.

I removed my shirt and bandaged my leg to stop the bleeding. I got so thirsty that I drank my urine. I decided to sleep under this big rock with the intention to wake up early the next day and hobble to the village.

Around 4am, I woke up and started hobbling back to the village. I got to a dry stream and was still thirsty. I used my hands to dig down hoping to find some water. After a while, I discovered that I could not get the water, so I started eating the wet soil. As someone who was very tired and badly injured, I decided to rest on the banks of this dry stream while lying down. As I hobbled to the banks of the stream, I forgot to clear my footprints. So I went and rested.

After a while, I think around 10am, I heard a hissing sound and I thought that maybe there was a snake nearby. I looked around, but could not see anything. From the blues, I saw a black soldier walking dressed in camouflage. I instantly knew that the Rhodesian forces were coming. I remained in my position. The Rhodesian forces saw my footprints and they all quickly took cover. They took cover while looking in the opposite direction from where I was. There were about 12 soldiers. For a while, they remained in that position. After a few minutes, one of the black soldiers stood up and climbed over a nearby rock to survey the surroundings.

MH: As this was happening, what was going through your mind?

WS: I said these soldiers are going to kill me in cold blood. I knew I didn’t have a gun, but somehow I looked around for a gun. Ndakanamata kuna Mbuya Nehanda ndikati ‘ndibatsirei ndava padambudziko rakakura kwazvo pano. Mabhunu aya ari kuda kundiwuraya.’

While surveying the area, this black soldier saw me and fell down in serious panic. He then came around that big rock and started firing at me. The first shot hit my right thigh, the next shot hit my left thigh and I could feel that one of my legs had broken. The next shot hit my hand, the next shot hit my right leg near the knee and I was hit on the back. This black soldier walked over to me and said: ‘let’s finish him off,’ while pointing a gun to my head.

A helicopter, I think that was supposed to come and take them, came and landed about 800m away. The pilot then shouted using a loud speaker that the black soldier was not supposed to kill me. The Rhodesian soldiers tied up my legs and started pulling me to the helicopter. The pilot, who I later knew as Doctor Staff, had come from Mpilo Hospital. He instructed these soldiers to lift me up and carry me to the helicopter. At first they resisted, saying I was too bloody, but the pilot insisted that they were supposed to carry me and not pull me to the helicopter. They later complied . . .

This was on October 23, 1975. I was taken to Mutoko where I was paraded in the open. As we were landing, I saw several helicopters and Rhodesian army vehicles that were riddled with bullets in the yard and I said to myself, indeed the enemy is feeling our war. Some Rhodesian soldiers came where I was and started interrogating me. Seeing that I was not willing to talk, they started beating me up. They wanted me to divulge secrets about our war strategy, but I refused.

The beatings were so severe that I later passed out. Remember, before they captured me, I had been injured and when the black soldier saw me, he shot me several times. Before receiving any treatment, they started beating me.

The pain was just too much and so I passed out. I was actually later taken to the mortuary because these Rhodesian soldiers thought I was dead. I had been certified as a dead person. You would think this torture was enough, but then that was just the beginning of this horror.

(He narrated how after being put in the mortuary, his soul and spirit drifted out of his body and went into this space above the clouds, where he met some of his long-gone ancestors. He said when he went to this place, his ancestors told him that it was not yet time for him to die. When he gained consciousness, the devil in his cruellest form was waiting for him.)

MH: So you came back from the dead?

WS: Yes! It was not yet my time to die, but to be honest with you, as I talk to you today, handione kunge ndiri kurarama. Muri kuita semuri kutaura nechipoko zvacho chemusango.

I am a dead man walking. Later I was taken into a spotter plane and I was taken to some place where about eight white soldiers started interrogating me again. I was put in a pool of blood as these soldiers were asking me all sorts of question. I am not even sure if it was human blood or not. These soldiers told me that they were from Britain and they wanted to understand how the war was progressing. They did not beat me at all. They were just asking questions. Later, I was taken to a hospital.

MH: When you got to the hospital, you were relieved that finally you were going to receive treatment?

WS: That is what I thought, but the real horror then started. The CID came and the interrogation started again before any treatment. When they started treating me, that is when I really saw the cruelty of the white man. Instead of amputating my right leg just above the ankle, they decided to amputate it just above the knee. I was not given any sedative to ease the pain. They amputated my right leg while I was watching using a hacksaw. It was as if they were cutting a tree.

MH: No, no, comrade, these people who were treating you were qualified doctors. How could they amputate your leg without giving you any drugs to ease the pain and how could they use a hacksaw?

WS: There was Dr Goosen, who was in the outpatients department. They chopped my leg using the hacksaw, wrapped the piece that they had chopped off in a cloth and put part of that bleeding piece right into my mouth saying; “come on, eat your flesh!”

MH: Comrade, is this real? Did this actually happen?

WS: Can’t you see I don’t have my right leg? I don’t have any reason to lie. They used the same method to amputate my left leg just above my thigh and I passed out. The pain was unbearable. By the time they cut your bones getting close to the bone marrow, kana anonzi anochema, hauchemi. Kana warwadziwa, you don’t cry. Ukaona munhu anorohwa oti ‘yowee,’ ziva kuti haasati arwadziwa. They had tied my hands to the operation table and so I couldn’t do anything. There are no words to explain the pain, but as you can see, I lost both legs in that horrendous torture.

MH: Did you plead with them when all this was happening?

WS: Pleading with who? Who would listen to you? Nobody! I took all the excruciating pain in silence. I just said to myself, “If this is your will God, let it be done. Help me to go through this. Even if helping me means me dying, Lord I am ready to finally come home.”

Surprisingly, I didn’t die. I spent about 10 months in hospital. After this, I was taken to Salisbury Maximum Prison where I stayed for about four-and-half years. I was in prison together with people like Cdes Maurice Gumbo, Moven Mahachi and others. There was no special treatment for me in prison . . . I was released from prison in 1980.

MH: You went through all this, you lost your legs. To you was the war worth it?

WS: I sometimes get angry, but ndizvo zvazviri. There is nothing I can do. If this had not happened to me, Zimbabwe would not be independent today.

I don’t even regret. If I had said I don’t want this to happen to me, we wouldn’t be where we are today.

To me this is what independence is all about. I am alive, but some comrades died. Struggle yakaoma. I am happy with the way I am living. If it wasn’t for sanctions, we would be receiving better salaries. But I am an optimistic person. I have a family and I am actually studying for a degree in agriculture. For me, the struggle continues.

**********************

Finally, the “dead man has died”. Go well gandanga! Go well Cde Gabela!