The Sunday Mail

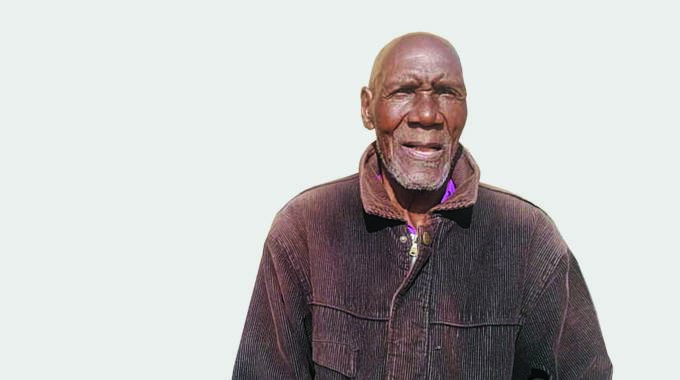

Misheck Mukwena of Mariwo Village in Bocha, Marange vividly remembers tragic events that unfolded in early 1979, in spite of his advanced age. On that dark day, a black Rhodesian soldier arrived at a homestead in Chikwariro Village and indiscriminately shot at villagers who were gathered for a traditional ceremony. Six innocent people, including two members of the Mhuriyengwe family, were shot dead in cold blood, while 17 other villagers were injured. One of the victims of the senseless rampage, John Makotamo, was shot on the hip. One of his legs had to be amputated. Makotamo is a living testimony and reminder of the cruelty and sadistic nature of Rhodesian soldiers, who, often times, shot and killed black people for no apparent reason. On the day, Mukwena watched helplessly and in horror as his elder brother was shot in the head. Sadly, the incident took place when the war had seemingly ended, with freedom fighters operating in this area having been taken to Dzapasi Assembly Point. In killing the innocent villagers, the Rhodesian army had breached the ceasefire agreement under which they had agreed to lay down arms and end hostilities. Our Senior Reporter TENDAI CHARA (TC) spoke to Mr Misheck Mukwena (MM) who recounted the incident.

TC: Mr Mukwena, kindly introduce yourself to our readers and narrate to us what transpired on that fateful day.

MM: My name is Misheck Mukwena and I was born in Mariwo Village in Bocha, Marange, in 1933. The incident occurred during the ceasefire period and freedom fighters were now in assembly points. My relative, Mr Gombe, who lived in Chikwariro Village, had brewed traditional beer and invited my family to come and take part in a traditional ceremony whose purpose was to thank the ancestral spirits for having ended the war.

I arrived at Mr Gombe’s home at around 9 am and I was tasked with serving beer to the more than 30 people in attendance.

We were seated in a circle outside the house as we drank beer while engaging in casual conversations.

Since I was the one serving the beer, I was seated right in the middle of the circle, refilling the cup and passing the beer to everyone present. As we were drinking and chatting, we heard heavy footsteps and immediately knew that Rhodesian soldiers were approaching.

The Rhodesian forces walked clumsily.

As soon as the Rhodesian soldiers got close, they started firing their guns and people scattered in all directions. Some of us, however, remained seated.

The Rhodesian soldiers split into two groups with one group chasing after those that were running away. The other group remained and walked towards us.

We were thinking that they were going to address us. As we were pondering what they might have been up to, we watched in disbelief and horror as a black Rhodesian soldier who was holding the Nato machine gun knelt into position and started shooting towards us.

I was holding a cup and when the soldier aimed his gun towards me, I dropped the cup and lay prone with my head leaning against the huge beer pot.

The freedom fighters had taught us how to react in such circumstances and I put those lessons into practice. A single shot rang.

Within moments, I was drenched in beer after the bullet hit the clay pot, shattering it into pieces.

I lay still, pretending to have died.

The Rhodesian soldier assumed that the shot had killed me, then aimed the machine gun towards the other people who were still seated.

White Rhodesian soldiers stood guard while pointing their guns at us.

They were ready to shoot whoever might have tried to escape. A hail of bullets was directed towards the group, resulting in six deaths.

Those that were killed were Jabavhu Makwarimba, Job Mukwena, Israel and Charles Mhuriyengwe, George Chitambira and Notai Bhasera.

Around 20 other people were injured, some seriously. As the black Rhodesian soldier, who had a Ndebele accent was firing, he took a brief break and started mocking us.

He was saying that those who were saying that the Rhodesian guns were ineffective were going to see for themselves that the guns were effective.

He only stopped shooting at us when he ran out of bullets. He was determined to wipe us out.

As he was in the process of reloading his gun, he was restrained by his white superior.

The black Rhodesian soldier went into a fit of rage.

He only stopped reloading his gun after the white Rhodesian soldier, who was leading the group, pointed a gun at him and warned him that he would be shot if he continued to reload the gun and shoot people.

TC: It was a harrowing experience…

MM: Horrific to say to least. After being shot, Mhuriyengwe repeatedly asked the Rhodesian soldier why he had shot him.

He asked the soldier the same question several times until he breathed his last.

Mhuriyengwe’s son Charles, who was also present, confronted the same soldier and repeatedly asked him why he had killed his father.

The Rhodesian soldier threatened to shoot Charles who, however, remained defiant.

I also watched in horror as my brother Job was shot at close range.

Because of the sheer power of the machine gun, his body was flung up into the air before it crashed back onto the ground.

As was the case with Mhuriyengwe, my brother Job, was also killed whilst close relatives watched. The scene of the shooting was terrifying. There was blood everywhere.

Some lost their fingers while others were shot on different parts of the body. After the shooting, we had a difficult time trying to find out what had killed Jabavhu Makwarimba, who had no bullet wounds.

At first, we assumed that he had died of shock.

We, later on, discovered that he had been shot in the heart and that the bullet was lodged in his body.

The black Rhodesian soldier who shot at us went into a rage when he, later on, discovered that his shot had missed me and that I was alive.

While hurling insults at me, the soldier tried to retrieve his pistol so that he could finish me off.

He was again restrained by his colleagues.

He tried, on several occasions, to shoot me but his colleagues saved my life by restraining him.

TC: In your view, why was the black Rhodesian soldier determined to shoot his fellow black people?

MM: I really don’t know. Maybe he wanted to impress his white superiors. During the war, some black Rhodesian soldiers exhibited some sadistic tendencies and were so desperate to impress their white commanders.

We had instances in which black Rhodesian soldiers tortured and killed innocent people and in most instances, they had to be restrained from doing so by their white colleagues. After the shooting, we were taken for treatment and medical examination.

TC: But how could the Rhodesian soldiers treat the same people that they wanted dead?

MM: I never understood why they did that.

Ripisai Bhasera, who was shot in the hip, was treated at the makeshift clinic and was later referred to Mutare where his leg was amputated.

After treatment, we were then allowed to take our dead relatives home.

It was a sombre atmosphere as families took the remains of their dead relatives home for burial.

One of our relatives who lived in the vicinity, Pikitai Kureba, provided us with a cattle-drawn cart that we used to carry Job’s body home for burial.

As we were on the way, we bumped into another group of Rhodesian soldiers who briefly detained and tortured us.

This time they were accusing us of breaking curfew rules.

We went home and buried our dead.

From that day, I was never afraid of the Rhodesian soldiers. I was defiant and always broke the curfew rules. I was prepared to die.