The Sunday Mail

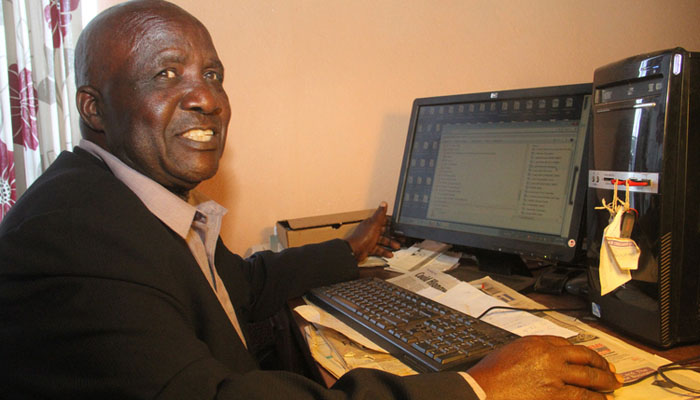

Thomson Kumbirai Tsodzo is a well-read man, in every sense of the word. As much as he is well-read himself, having read for a Doctor of Philosophy degree at Michigan State University, he has been read by quite a number of people.

Those who might not have read his debut publication, “Pafunge” (probably the most famous of his works), might have read him as the “notorious” political commentator Silas Murombomunhu in Moto magazine back in the 70s. Still those who might have missed these instalments, might have studied his “Rurimi Rwamai” Shona textbooks in secondary school.

And if you have been unfortunate to miss all these three episodes, don’t despair for TK Tsodzo is not yet done with you.

“Besides scores of unpublished works that I am sitting on, I am working on reviving our local film industry and have loads of scripts that I think will help to kick-start the sector,” he said in a wide-ranging discussion at his Marondera farm last week.

Whilst the name TK Tsodzo might ring a bell to many as a respected author and academic, it is the “subtle” role that he played during the liberation struggle that he is always eager to talk about, his days as the all-conquering teacher at Kwatsambe, as St Augustine is commonly referred to.

After graduating from the then University of Rhodesia with a BA (General) in Languages in 1971 — the same year his ground-breaking “Pafunge” was published — he enrolled for a Graduate Certificate in Education and upon completion went to Old Umtali Mission to teach.

By then the liberation struggle was gaining momentum, with some of the liberation fighters based in Mozambique.

“The late Cde Josiah Magama Tongogara had two bodyguards, Cdes Chamunorwa Zvipange and Stephen Musorowunobaya. You might know them as Oppah Muchinguri and Stephen Tsodzo respectively. Stephen was my brother and through him I got my early political orientation.

“Old Umtali where I was a teacher was under the control of Bishop Abel Muzorewa’s church and it wasn’t long before we differed ideologically. And because of the high grades that my students attained at the school, I did not need any convincing to St Augustine, which was nearby and also a rival, when I alerted them of my desire to leave Old Umtali.”

The more TK Tsodzo interacted with his brother and the others in Mozambique, the more his interest and co-operation with the execution of the liberation struggle grew.

“We would take students to Mozambique for training and bring those who had been trained back into the country for deployment.

“And at times this was heart-breaking because I was losing some of my bright students to the struggle.

“I remember Rita Makarau left for military training just before she wrote her examinations and she had to complete her education by correspondence when she came back from the struggle.

“Chris Mutsvangwa left just after writing his examinations and only collected his results after he came from the struggle. Nyasha Chikwinya was also my other student, she just left like that.”

That he mentions Mutsvangwa, was he always that verbose, in school? “Chris was an intelligent student. To say that I taught him would be lying, there are things that he would tell us as teachers and we would just wonder where or how he got that information.”

Whilst he says his students are too numerous to mention and remember, one name that he remembers with ease is the late Solomon Mutsvairo who set him on the path to fame.

“Mutsvairo was my teacher at university, teaching me languages. By the way, I wanted to be a lawyer, then drawing a lot of inspiration from Herbert Chitepo, who was my uncle’s friend. But only two black law students were enrolled in the year that I went to university, therefore I had to take Languages — Shona, Latin and English.

“So Mutsvairo would ask us to write essays in our languages class and when I wrote one, he came to ask how I had thought of that storyline. He prodded me to expand on the story and possibly turn the story into a novel. That is how “Pafunge’ was born and got published in 1971. It was an essay turned into a novel.”

Then the other ground-breaking moments came during his teaching days. “At that time most of the Shona teaching material was written by whites and some of the translations and usage of words were wrong.

“So as someone who had studied languages at university, I would prepare tutorials for my students. Some of the tutorials went viral, to borrow today’s terminology, and got the attention of education officers, who then implored me to publish the tutorials into textbooks. That is how the “Rurimi Rwamai” series was born.”

Usually God does not gift you everything. His prolific writings was not matched by his oration, a weakness that his wife readily testified to. “If it was not for (the late) Witness Mangwende, he would not have won my heart,” quipped Mrs Miyedzoyashe Tsodzo, his wife of 45 years.

“I first saw her in 1959 when she came to Makumbi Mission and I knew I wanted her. I proposed but she turned me down, probably because I am ugly,” laughed off Tsodzo, the husband.

Two years later, as fate would have it, she was to join him at Zimuto, him doing Form 4 and her doing Form 1. The romance rekindled, albeit with her standing her ground. Until the intervention of Mangwende.

“I was more clever than him and I remember when I asked him why he loved me he failed to convince me, until Witness intervened on his behalf,” another hearty laugh from the wife.

They were to marry in 1972 and have been blessed with two girls — Rudo and Vimbai and one boy — Munyaradzi. “I was so good with my books that most of my learning has been through scholarships. In fact, my legacy was so good that I had to leave Vimbai at Michigan State University where is currently teaching,” added Tsodzo.

But it is his days at the University of Rhodesia, when he was a part-time teacher, that had so many life-changing moments for him. “I acquired my diplomatic passport during those days, and I still have it up this day. And it is with the diplomatic passport that I travelled, mostly, to China to buy arms for our liberation and sent them to Tanzania, at which Nathan Shamuyarira, who was teaching at Dar es Salaam University, would receive them.”

But how did he acquire a diplomatic passport those days, when blacks were so looked down upon? “First, it was with the help of Kumbirai Mukanganwi, who was my lecturer together with Mutsvairo and George Kahari, who assisted me acquiring the passport. Second, I was a ground-breaking teacher, my students were passing so well so it was not difficult to convince anyone to get anything for this record-breaking teacher.”

Another prized possession from back in those days is an AK rifle. “I got that when I was assisting students into Mozambique and guerillas back into the country. I was given it just in case but I never used it, even up to now.”

Seemingly glowing, he remembers something. “Yes, there is another interesting anecdote from the liberation struggle. Mutsvangwa was a good singer in the church choir, so he would cross in and out of country, in and out of school. So when we were crossing into Mozambique, and if we were about to encounter a roadblock, the students would break into song and Mutsvangwa would lead in its singing. Remember they would all be wearing school uniforms.

“The song was a popular Anglican hymn but it had been corrupted into a liberation war song and no-one picked it up. And it is for that small role that I played in ferrying students and guerillas that I was named ‘Commander’, not that I was any field commander.”

Yet another story. “You have probably heard of the bombing of the petrol tanks in the then Salisbury? Seven of the guys I drove them to the bombing. One of them, Silas Taika, is still alive and was once married to my wife’s sister, the wife sadly, passed away.

“I drove them from my Harare home and left them just near Harare Hospital – I knew what they were up to but I never them saw after the attack.

“Guerillas would never assemble at the same point after an attack, they would go in separate directions.”

Is all this material in the scripted movies? “Some yes, some are just social issues. Film must be diverse and touch all other aspects of people’s lives.”