The Sunday Mail

Golden Sibanda

Senior Business Reporter

AS projected by Finance and Economic Development Minister Professor Mthuli Ncube, Zimbabwe appears headed in the right direction in the quest to tame what essentially has been galloping inflation since October 2018.

Zimbabwe may now be well poised to end the year within Minister Mthuli’s targeted monthly inflation range after the November rate plunged nearly 50 percent, having seen largely exponential increases for much of this year.

Minister Ncube predicted in October this year that on the strength of measures taken by the Reserve Bank of Zimbabwe (RBZ) to tighten money supply and reverse (hot) money growth; aimed at fostering exchange rate stability, the monthly inflation rate would decline to around 10 percent by December 2019.

Such a trajectory would also work to force a gradual decline (on price stability) of the rate on an annualised basis.

Treasury has also rationalised its expenditure and expects to end the year within its budget deficit target of 4 percent of Gross Domestic Product after it also desisted from using the RBZ overdraft window to fund State projects.

Further, the RBZ indicated that while it was targeting an ambitious annual money supply growth rate of 10 percent by year end. Money supply growth had already increased 80 percent in the eight months to October.

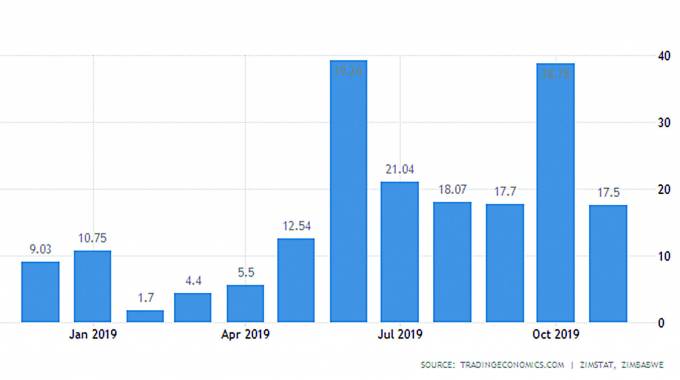

And according to Zimbabwe National Statistical Agency (ZimStat), the November inflation on a month-on-month basis dropped from 38,75 percent in October 2019 to 17,6 percent on account of relative exchange rate stability.

Publication of annual inflation figures was suspended in July, following the reintroduction of domestic mono-currency, to allow like-for-like comparison of inflation trends using prices data based on the same currency. When Zimbabwe suspended publication of the annual rate, it had reached 175,6 percent for June 2019.

While the annual rate is estimated to be higher than the last official rate, monthly trend appear to be taking a trajectory envisaged by Treasury in the quest to ensure prices and inflation stability.

Inflation in Zimbabwe took off in October last year after the RBZ directed banks, amid growing US dollar shortages, to separate foreign currency and (RTGS) accounts while maintaining the exchange rate at 1:1.

Zimbabwe’s official floating of the exchange rate in February this year gave impetus for price instability, as importers and producers would factor in the cost of getting the hard currency to bring in or make products.

The local currency has lost considerable ground against major currencies since being floated in February at US$1 to $2,5 with the exchange rate now trading around $16,6 against the greenback on the forex interbank market.

The Southern African country is dependent on imports, with industrial production only averaging 40 percent, which creates significant pressure on demand for foreign currency, an inflation transmission medium.

As such, each time the rate moves up, it has significant pass-through effects on prices and cost of production.

“Government’s main hope for January is that the foreign exchange black market, which has been driving the retail prices of goods and services, will be brought under control,” said economist Mr John Robertson.

“If that is achieved, the high monthly price increases seen recently will become much more modest and permit the annual (inflation) rate to start falling by about the middle of 2020,” Mr Robertson said last week.

Remarkable variations in cost increases over the 12 months to November were seen across the range of goods and services. Prices of vehicles, including motorcars and bicycles, increased by more than 1 000 percent.

Apart from vehicle spares, other items in the 1 000 plus percent range include passenger transport fares, car insurance and pharmaceuticals. In terms of food items, only seasonal fruit prices increased by more than 1 000 percent.

Non-food items constitute the biggest chunk of products considered when calculating inflation, about 70 percent of the weight of the consumer basket while food and non-alcoholic beverages make up the balance.

However, it is worth noting that exchange rate dynamics are also a function of liquidity with previous unrestrained Government expenditure blamed for excesses liquidity that has been pushing up exchange rates.

This resulted in significant money supply growth or hot money, borrowed through Treasury Bills used to finance recurrent budget deficits and some programmes that were not factored in the National Budget.

Going forward, the Reserve Bank needs to maintain a tight leash on broad money supply, which drives demand for foreign currency thereby pushing exchange rates up, making it a tool for inflation transmission, said Zimbabwe National Chamber of Commerce (ZNCC) chief executive officer Mr Takunda Mugaga.

“I think you heard the minister in his 2020 National Budget saying we expect the Reserve Bank to complement efforts to fight inflation by controlling money supply growth. That was Section 51 of the Budget.”