The Sunday Mail

Tjenesani Ntungakwa

After the Wankie and Spolilo campaigns of the late 1960s, it was apparent that Rhodesia was at war.

The boundaries shared by Rhodesia and her neighbours became porous conduits for guerrilla infiltration.

Rhodesia’s white population was on record as one of the heavily armed civilian communities in Africa.

By the early 1970s, Africa’s Portuguese colonies were on fire. There were certain variables that made the Rhodesian scenario different.

Whereas pro-worker movements had some room for activism in England, they were completely shunned by authorities in Lisbon. The Portuguese intelligence organisation, Pide, spread its wings into African colonial territories.

There was also a prevailing ideological posture on the part of the working class in Europe to control of the means of production as a step towards full emancipation.

Such premises of thought were partly influenced by Karl Marx.

Old and frail, Karl Marx spent his last years in Britain.It was from Marx’s observations that some militant trade union platforms began to emerge in post-World War II Europe.

They challenged the yoke of laissez faire capitalism and worried political structures, particularly in Portugal, Germany and France.

It was this that made the British feel that the future of Central and Southern Africa was vulnerable.

The matter was further compounded by the fact that a Rhodesian rightwing formation won the 1962 elections.

Initially led by Winston Field and then Ian Douglas Smith, the Rhodesia Front became the bastion of settler colonial power.Rhodesia was slapped with punitive sanctions after the UDI of 1965. Britain started leaning towards constitutional, rather than militarised, solutions to the Rhodesia question.

The other side of the equation dictated that Zanu and Zapu, which were banned in Rhodesia, could not take part in the manoeuvres for constitutionalism.

The so-called Anglo-Rhodesia Constitutional Settlement proposals were agreed in Salisbury on November 24, 1971.

The British government under Sir Alec Douglas Home found it necessary to subject the proposed framework to what was referred to as a “Test of Acceptability.

Such a test would ensure that that the preferred conceptual order in Rhodesia was adopted as “legitimate”.

For that reason, the British put together a team to go into various districts of Rhodesia and seek the views of its citizens.

A commission under Lord Pearce was put together. In his contingent were Sir Maurice Dorman, Lord Harlech, Sir Glyn Jones, Mr THT Cashmore, Mr GC Rawlings, Mr JE Blunden, Mr PL Burkinshaw, Mr GRB Blake, Mr DF Frost and PA Large.

Most of those in the Pearce Commission had worked in the British Overseas Service, making them “political technocrats”.

Before the Pearce Commission arrived in Rhodesia on January 11, 1972, there were some reactions on the ground which influenced the direction of the events to follow.

The Nnationalist organisations and their leaders were wary of the Anglo-Rhodesian Settlement.

As Arthur Chdazingwa put it, “If the Settlement Proposals had been accepted, it was going to make the fight against the settler colonialists much harder than it had already been. If accepted, the propositions would further entrench the power of the UDI government and come up with an isolated and highly discriminatory regime like the Apartheid establishment in South Africa, some kind of independent white republic in Africa.”

Basing on such possibilities, it was necessary for Zanu and Zapu to mobilise against the Anglo-Rhodesia proposals.

From a practical point of view, organising anti-Settlement support was not going to be easy because the Zanu and Zapu had been banned.

It so happened that some clergymen had been very active in highlighting the problems of Rhodesia from the pulpit and their stance became an open secret.

One of them was Reverend Canaan Banana, who had something to do with the Zimbabwe Peoples’ Movement.

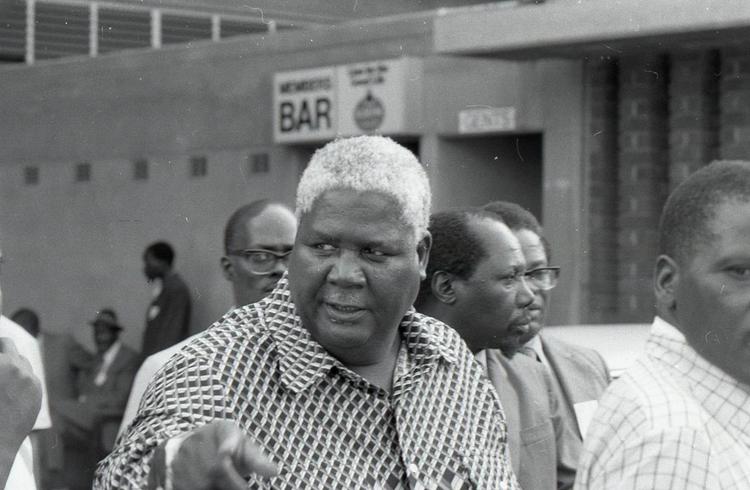

Bishop Abel Tendekayi Muzorewa of the United Methodist Church was another visible character in that regard.

Muzorewa and Banana seemed to have access to the detained Zanu and Zapu leadership.

In his brief history of African National Council, Gordon L Chavunduka gave an account of how the ANC was unveiled on December 16, 1971 before the Pearce Commission touched down in Salisbury.

Some of its leaders were Bishop Muzorewa, Rev Banana, Charlton C Ngcebetsha, Michael Mawema and Dr Edison Sithole.

From the onset, it had some membership of Zanu and Zapu office-bearers like Edison Zvobgo and Josiah Chinamano.

Chinamano, Zvobgo and Naison K Ndhlovu were among those who had been released from incarceration.

The ANC was intended to educate and advise Africans on the long-term dangers of accepting the Anglo-Rhodesia Settlement proposals.

It was not a political party and did not even have an assured lifespan.

An unforeseen contradiction showed up. In anticipation of the Pearce Commission, the Rhodesian Centre Party began to recruit from among African teachers.

It played around with the anti-racist rhetoric though it remained a massive white forum with leftwing fervour.

When the Pearce Commission finally came to Rhodesia, the ANC had already embarked on its rounds.

The commissioners went to various places where the locals gathered to hear about the Anglo-Rhodesia Constitutional proposals.

In one instance, the commission visited Musana Village in the first week of February 1972. Having brought about 2 000 people under his jurisdiction, Chief Musana was reported in The Herald of February 4, 1972 to have told the crowd that whites were long-standing friends of the Rhodesian people.

The paper said the chief was booed until he spoke against the Anglo-Settlement proposals.In another incident, a deputation of the coloured community in Bulawayo met Pearce commissioners in early February 1972 and urged the commission to take a serious look into racial discrimination.However, they accepted the settlement terms though with some “reservations and doubt”.

The association’s representatives were Mr J Van Beek, then chair of the National Association of Coloured people, Mr Schoeman (president), Mr J Durk (secretary) and Mr Mike Joseph.

The ANC had misgivings with the method with which the Test of Acceptability was administered.

As far as the ANC was concerned, the only acceptable mode of testing the will of Rhodesia’s peoples was “one man one vote”.

The ANC expressed disapproval of continuing State of Emergency, and also dismissed the Anglo-Rhodesia Settlement proposals as a replication of the rejected 1969 constitution.

On the intended House of Assembly, the ANC criticised the creation of three voters’ rolls which perpetuated racism.

The criticism of the African Higher Roll went as far as the implications of Land Tenure Act, which made it difficult for Africans to acquire immovable property.

Disapproval of the Senate was based on the fact that it was interpreted to be “undemocratic and racial”.

The ANC had looked into other aspects of the proposals like The Declaration of Rights, Renewal of the State of Emergency, Detainees and Persons under death sentence, Land, Development Programmes for Africans and the Rhodesian Public Service which had traditionally been a reserve for whites.

In total, the ANC were of the opinion that the Anglo-Rhodesia Settlement proposals were not a satisfactory arrangement for the majority in Rhodesia.

The “No” vote won the day.

Lord Pearce and his men packed their bags and left for Britain on March 10, 1972. On that day, the ANC transformed itself into a political party.The ANC indicated that the journey to Zimbabwe would continue in a Christian and non-violent manner. It declared belief in the unity of Zimbabweans and non-racial conduct. Minority property and universal human rights were to be protected.The ANC held a congress on March 2 and 3, 1974 at Stodart Hall, Harari Township (Mbare).In its structures were a national congress, general executive council, national executive council, provincial conference, provincial executive, district conference, district executive, branch executive, women’s league, youth league and so on.In 1975, the central committee of the ANC had the following composition: president AT Muzorewa, deputy president EM Gabellah, secretary-general GL Chavunduka, treasurer-general Rev HH Kachidza, deputy treasurer-general Mr R Nyamweda, national organising secretary KB Bhebe, publicity secretary Mr SB Mthinsi, deputy publicity secretary J Ntunta, secretary for youth Mr ST Bongi and others.The closest that the ANC came to some celebrated achievement was the December Unity Accord.

On December 7, 1974, in Lusaka, Zambia, Zanu, Zapu, Frolizi and the ANC met under the auspices of the Zambian government to discuss and finalise a unity treatise.The consenting parties would appoint three representatives each to an enlarged national executive. It was agreed that within four months, Zanu, Zapu, and Frolizi would work to merge their structures into the ANC before hosting a congress.

Those who appended their signatures to the “deal” were, Bishop Muzorewa (ANC), Dr Joshua Nkomo (Zapu), Rev Ndabaningi Sithole (Zanu) and Cde James Dambaza Chikerema (Frolizi).

An application dated December 11, 1974 was sent to the Executive Secretary of the OAU Liberation Committee seeking recognition of the ANC as the sole representative of the African political struggle in Rhodesia.

The Liberation Committee met in Dar es Salaam from the 8th to the 14th January 1975 to consider this.

On January 10, 1975, the OAU recognised the African National Council as the representative movement of the African people in Rhodesia.

A resolution was adopted by the leaders to work together. After the 74 Accord, the ANC enlarged its Central Committee to accommodate Rev Sithole, Dr Nkomo, Cde Joseph Msika, Cde E Nkala, Cde L Nkala, Cde Malianga, Cde Willie Musarurwa, Cde Robert Mugabe, Cde Chikerema, Cde Nyandoro, Cde GS Parirenyatwa and Cde L Munyawara.

Within the ANC, the December 1974 Accord did not effectively translate into a comprehensive pact for Zapu and Zanu.

In the longer run, it was a risky engagement. Outwardly it could be tempted towards flirting with the Rhodesia liberal agenda.

For its survival, Rhodesian settler intransigence had always made an effort to court religious leaders like Bishop Muzorewa and Rev Banana.

On a conciliatory note the ANC lobbied strongly for the release of more detainees. In the mean time, disagreements between Zanu and Zapu resurfaced.

The feeling was that the ANC was an obstacle to the armed struggle because it kept everybody who mattered in closed discussions thus undermining the efforts for a confrontational strategy.

In January 1975, an ANC delegation was expected in Lusaka, Zambia, to meet British foreign secretary James Callaghan.

Among the possible troupe were its Dr Elliot Gabellah, Dr Nkomo, Rev Sithole, Dr Edison Sithole, Rev Kachidza and Cde Edgar Tekere. Callaghan’s principal aide, John Ackland, was already in Lusaka for preliminary talks.

In July 1975, Presidents Kaunda, Machel and Nyerere, were expected to meet with a 12-member ANC team to discuss ways of ensuring orderly co-ordination in the organisation.

In the last week of July, 1975, John Nkomo, ANC administrative secretary Cde George Nyandoro and Cde Simpson Mutambanengwe were destined for the OAU Summit in Uganda.

However, the shuttling and shuffling never gave a long life to the ANC. Just like the attempted JMC, the ANC succumbed to the vicissitudes of time.