The Sunday Mail

Dr Ranganai Gwati

Last week, The Sunday Mail published the first of academic Dr Ranganai Gwati’s three-part series on why Zimbabwe should exclusively adopt the South African rand. Below is the second instalment.

***

According to statistics from the Reserve Bank of Zimbabwe, 88 percent of Zimbabwe’s Diaspora is in South Africa, and the highest percentage of remittances, at 33 percent, comes from there (May 2015).

According to statistics from the Reserve Bank of Zimbabwe, 88 percent of Zimbabwe’s Diaspora is in South Africa, and the highest percentage of remittances, at 33 percent, comes from there (May 2015).

I examine the effects of depreciation of the rand against the dollar on GDP via remittances. A depreciating rand reduces the incentive to send money home for South African-based Zimbabweans.

I use an anecdote-inspired example to illustrate the inter-linkage between a depreciating rand vis-à-vis the USD, remittances from South Africa and the informal sector.

It’s worthwhile to note that GDP, a measure of the value of final goods and services produced in a country’s economy and a frequently-used measure of standard of living, can be measured as the value of household consumption, investment, government expenditure on goods and services and net exports (GDP=Consumption+Investment+(Exports-Imports)+Government Expenditure).

Consider Trymore, a Zimbabwean who works in South Africa and sends R3 000 every month.

The money is to build a house (what an economist would consider an investment). Then there is Loveness, another South African-based Zimbabwean who sends R1 500 every month for her mom to pay rent and buy groceries (consumption).

Suppose the exchange rate starts at R10 to USD1, and the rand depreciates to R15 to USD1.

I investigate the expected effect of this rand depreciation on each of the components of Zimbabwe’s GDP.

Investment channel: Initially, Trymore’s remittances of R3 000 were US$300 in Zimbabwe. After depreciation, it only gets him US$200. Since prices haven’t changed in Zimbabwe, it becomes too expensive for Trymore to continue building.

The builders have to be laid off and join the informal sector, further suppressing profitability in that sector.

Consumption channel: Loveness’ mom will not be able to buy as much groceries as before because she now receives only US$100 from her daughter, down from US$150.

As she and others like her reduce consumption, domestic firms have to reduce production since demand has decreased.

Net exports channel: Zimbabwean firms have to reduce production and retrench workers since their market has been reduced because their domestic customers are going for cheaper South African-produced goods, and their South African customers are finding it more expensive to buy Zimbabwean-produced goods.

Government expenditure channel: Government spending is typically financed from taxes, borrowing or seigniorage. (The profit made by governments from printing more money. Seigniorage is calculated as the value of the money minus the cost of printing the money).

The three channels above imply tax revenue will go down.

Government loses a source of income tax revenue as workers move from the formal sector to the informal sector because in the informal sector, it is extremely hard for the government to collect taxes. The decline in tax revenues is worsened by the fact that seigniorage is not an option since the Government of Zimbabwe does not have its own currency and borrowing is complicated and expensive because of Zimbabwe’s credit history.

Based on the above, a depreciating rand unambiguously leads to a decline in Zimbabwe’s GDP, via the remittance-plus-informal-sector channel.

The extent of this drop is huge because the largest proportion of Zimbabwe’s Diaspora community is based in South Africa.

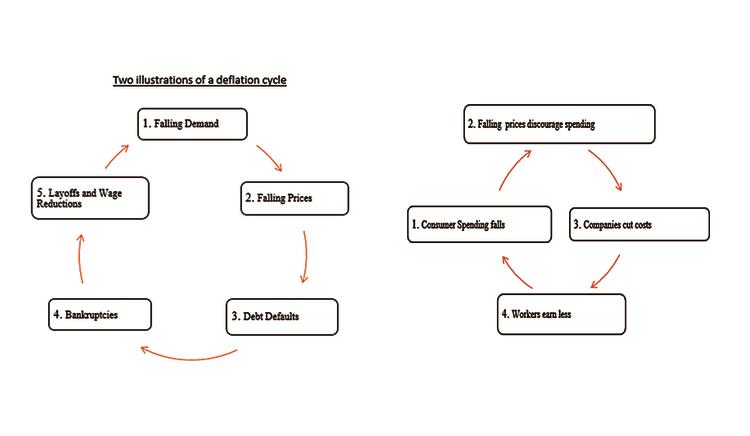

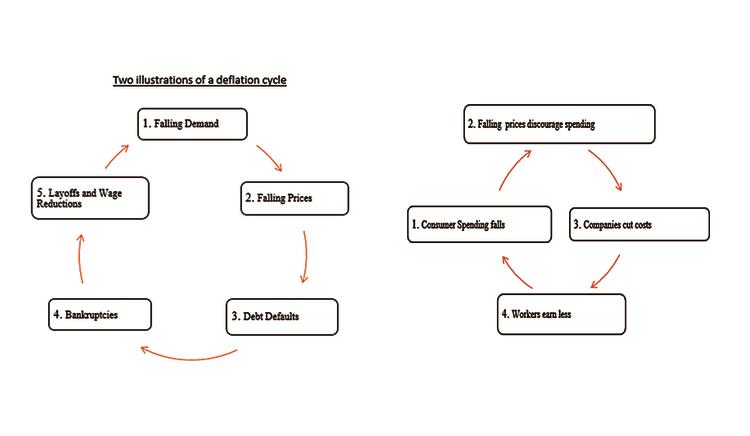

It is, therefore, unsurprising that there have been signs of worsening deflation (a general decrease in the price level) in Zimbabwe as the rand depreciation intensified.

Taking advantage

I will briefly point out potential problems with some recent perspectives regarding the rand depreciation (“SA’s loss is Zimbabwe’s gain”, The Sunday Mail, January 10, 2016; and “Take advantage of weak rand, says RBZ boss”, The Herald, January 16, 2016).

In The Sunday Mail article, the author opines, “Zimbabwe can capitalise on lower prices obtaining in South Africa and other emerging markets facing currency depreciation to import some machines and retool its industries.”

In The Herald, RBZ Governor Dr John Mangudya is quoted as saying, “This might be the time for Zimbabweans to import capital goods from South Africa at a cheaper price and invest in Zimbabwe and also produce at a lower cost.”

I find these analyses problematic on several grounds. The incentive to invest is driven by a positive outlook on the state of the Zimbabwean economy so that potential investors can expect a positive return.

At present, there are few signs that local demand will soon increase and that Zimbabwe’s producers will not continue losing regional competitiveness due to use of the USD. Local company owners will likely need to borrow to finance purchase of machinery because of current low productivity levels and liquidity issues.

When an economy is in deflation, the real value of debts increases, making it harder for borrowers to pay back, increasing the risk of default. Because risk of default is higher, banks are less willing to lend.

A simplistic illustration: Suppose I borrow US$10 from my friend, Goodmore, to buy 10kg of mealie-meal. Because of lower demand, suppose the price levels went down 50 percent and that my work hours were also halved (instead of cutting my wage in half, there is contract!). The 10kg of mealie-meal now costs US$5, but I still owe Goodmore US$10!

It’s now harder for me to pay back the same US$10 because it’s now worth more goods and services.

The analyses in the aforementioned articles ignore the reduction in investment and consumption through the remittance channel.

Thus the argument that Zimbabwe can benefit from the rand’s depreciation by acquiring capital and boosting the investment component of GDP is problematic.

Exclusive rand adoption

I now consider some of the policies Government can implement to help kick-start the economy under a rand regime.

Exclusively adopting the rand can give Government the rare opportunity to directly and indirectly force a restructuring of the pricing and wage model.

One of the drawbacks of the USD-dominated regime is that it sustains profiteering ushered in by the prior hyper-inflationary period.

During the hyper-inflationary period, production grounded to a halt as both capitalists and labour downed tools in search of “fast money” from foreign exchange arbitrage.

The prolonged existence of this period meant a culture and generation of “fast money” was born and when dollarisation was adopted, the culture persisted.

These ambitious entrepreneurs used the property markets to bank proceeds of their foreign exchange arbitrage, driving the market to unsustainably high levels.

Eight years later, Zimbabwe is stuck with an overvalued property market that only one percent of the population can afford.

For example, it’s hard to imagine how a family of five, making US$500 a month can afford a US$30 000 house in Chitungwiza.

These prices have remained high despite extremely low disposable income in the country because of:

(i) the Diaspora population has been willing to spend on property to show fruits of their adventures abroad; and

(ii) the fast money capitalists are reluctant to offload their properties at a loss as they still regard property ownership as one of the safest ways of storing value.

High prices have also persisted in consumer goods due to a combination of fast money culture (capitalist profiteering), industry low efficiency, high taxes, and unreliable and expensive energy.

As I argued earlier, the rand will help drive consumption, which reduces profiteering as capitalists enjoy higher sales volumes and are willing to cash in their property investments to invest in a growing consumer industry.

Current stagnation in the consumer sector makes the reasons to dispose of these properties at a loss in order to gain liquidity less compelling as there are no alternative investments.

Marking prices in the rand will force consumer prices to converge to regional averages as consumers can easily compare prices of goods between South Africa and Zimbabwe without going through the headache of calculating the dollar equivalent.

For example, a loaf of bread costs R10 in South Africa and US$1 (R15) in Zimbabwe, or 50 percent more at the current exchange rate of 1:15.

Such huge price variances are easily masked when consumers are comparing rands and USD, but become glaring when looking at rand prices in both South Africa and Zimbabwe.

Once labour and other resources are priced in rand, it becomes easier to compare efficiencies between industries across the border.

Assuming comparable energy and input prices between South Africa and Zimbabwe, if Zimbabwean farmers after converting to a rand economy are still producing eggs at two times the price in South Africa, the Government of Zimbabwe should allow South African eggs to be consumed in Zimbabwe.

It will be senseless and wasteful for Government to protect such inefficient farmers. Today, the arguments can be made that Zimbabwean eggs are simply more expensive because the USD is expensive and such arguments will fall away when the USD is replaced with the rand.

Zimbabwean industries will have to adapt structurally to be competitive once labour and resources are priced in Rand.

Any arguments about an expensive currency as the reason for higher prices will no longer hold water.

Dr Ranganai Gwati is Assistant Professor of Economics at Benedict College (South Carolina). He holds a BA in Mathematics & Economics from Reed College (Oregon), where he got the Meier Award for “distinction in the Reed undergraduate Economics curriculum”, and Master’s and PhD degrees in Economics from the University of Washington (Seattle), specialising in International Finance. At UW, he also obtained a Graduate Certificate in Computational Finance. Dr Gwati acknowledges contributions from FS Nyangore (Rusape).