The Sunday Mail

Text: Garikai Mazara, Prince Mushawevato

Photography: Believe Nyakudjara

Chiadzwa diamond fields in the Marange communal area lie some 120km south-west of Mutare – Zimbabwe’s fourth-largest city.

When driving to Chiadzwa, down the winding and tarred 80km stretch from Mutare up to Hotsprings, which for all intents and purposes should be a memorable drive for any first-timer to the area, one will be excused for conjuring images of Kimberley, South Africa’s diamond nerve centre.

An illegal miner makes his way out of the Chiadzwa Mining Field with his loot

But upon arriving at Hotsprings, also known as Nyanyadzi, that air of expectation self-corrects.

For their part, the Hotsprings – a natural wonder if ever there was one – have largely remained neglected, and it seems the 10-year diamond rush to nearby Chiadzwa never had any impact here.

That air of expectation that disappears upon arriving at Hotsprings gets to a level of frustration as one drives into the heartland of Chiadzwa.

Despite years of mineral extraction by the mining companies in and around Chiadzwa, the communities still struggle to access water for domestic use

Despite years of mineral extraction by the mining companies in and around Chiadzwa, the communities still struggle to access water for domestic use

Despite years of mineral extraction by the mining companies in and around Chiadzwa, the communities still struggle to access water for domestic use

The high level of police activity is to be expected given the security nature of diamond fields, and the frustration is more from the state of the roads.

When one knows the kind of wealth that has been dug up from here and flown all over the world, the frustration can become dejection.

The first port of entry is manned by Republic Police and the Army. This is the first of three round-the-clock roadblocks one encounters.

On either side of the road are hills of earth that tell the story of a land that has opened up and revealed the bountry lying beneath.

The inverse of the hills are gullies, which in past years were welcomed by freely roaming cattle that used to drink water here before the drought hit us.

There have been attempts to reclaim some land. But it appears these attempts were either hurried or half-hearted. Who wants to spend money on reclaiming land when there are diamonds to be dug up? Then at the centre of the fields is what should, all things being equal, be the town centre of Chiadzwa. Your Kimberley, if you please.

But Chiadzwa is a township, for lack of a better word. In fact, some townships elsewhere in the country that haven’t experienced a diamond rush are better-developed, infrastructure-wise. Your Mverechena, for example.

But here is Tenda shops, rather township, where the gwejas, a euphemism for panners, while up their time as they wait to pounce on the diamond fields of Chiadzwa.

If they are not killing the hours, they are waiting for the guy in the white Toyota twin-cab, the usual and trusted buyer, to show up.

The panners all agree that the fields still have something to offer. On an average day, the panners say, one can get anything between US$20 and US$100.

“That is the usual story, something to get you going, to get you food as you get in and out of the fields. But there have been the rare cases of those who can hit US$5 000 in one swoop. Even US$50 000. We have heard stories of panners who made as much as that. But it is not everyday, those are rare instances,” says one man with a hopeful gleam in his eyes.

The “diamond rush” in Marange communal lands started around 2006 and it looks like – 10 years later – that rush has come full circle with the announcement by Government that the five diamond companies operating in the area should cease operations and join one consolidated State-led company.

The companies have been resisting the move, naturally. Of course, the illegal panners moved back in: stealing property, cutting security fences, and looking for the precious stone in areas that the companies used to operate in.

“It is quite dangerous to be here my brother,” one of the panners says. “The options that we have are very limited. It is not like we want to be here, especially if you consider the treatment that we get when we are caught, no one would want to be in this situation.”

The panners risk life and limb as they try to evade the police and the Army, and their dogs. “It is difficult to say which is better, to be caught by the dogs or the people,” one fellow says.

The panners say as much as the police and army details are armed, they are not in the habit of firing their weapons.

“But like I have told you my brother, you wouldn’t want to be caught by those guys. But then again, there is little choice for us, that is why you find us playing this hide-and-seek game.”

Headman Mukwada, like much of the Chiadzwa community, is unhappy with the level of plunder of natural resources vis-à-vis development of the area.

Headman Mukwada, who has oversight over 18 villages, has no kind words for the diamond companies that have been involved in Chiadzwa, companies which were ordered to cease operations by the Government this month.

“When these companies came, they promised us a lot of things. They said we will have tarred roads within two years, have electricity, schools and clinics – but all that has just been talk.

“I think you have seen for yourself the road that you used from Hotsprings. If you go the other way, it is even worse. And yet diamonds were leaving this area almost every week – the plane would leave at least twice a week. Where is the money? Where is the development that they promised us?”

“The move by the Government,” he adds, “to consolidate the companies into one company might be welcome. Maybe if it is the Government that is to be involved, they might have a different take to our welfare. As for these private companies, we have already seen that they didn’t live up to their promise. Hopefully the Government will not let us down, as did the diamond companies.”

He also sees the irony in the private companies’ resistance.

“If these diamond companies are saying that there are no more diamonds in the fields, then why are they refusing to go? That should tell you that they are lying, our diamond fields still have a lot to offer.”

Though the area is heavily cordoned, with a heavy security presence, the panners always find a way into the Chiadzwa diamond fields. Those from Buhera will have to tackle the Save River and into the fields, they will be. Once inside, they join locals in a hide-and-seek game.

“Usually we get in at night and smuggle the samples from the fields. The downside to night panning is at times, which is more often, you carry a lot of stuff that you won’t need. Unless you are extremely lucky, night panning is arduous. But then again, day-time panning is risky, as you can see the police (are) all over,” narrates one panner, who had made the journey from Watsomba.

In such a security-tight environment, getting an interview is not easy.

Those who speak do not want their identities revealed. And their story is the same: the private companies negelcted them. Rombe Primary School is desolate and has four make-shift classroom “blocks” made from pole and thatch.

“That recently completed classroom block,” one parent informs us, “was the work of the Chinese. Otherwise, if they had not built that block, the whole school would be those four shades.”

Gandauta Secondary School, which the diamond companies had promised to help electrify, remains in the dark.

Mr Farikayi Njeza, an aide to Headman Mukwada, says many pupils have to travel anything up to 15km to reach a school.

“We were promised schools and clinics but since the diamond companies moved in, that is some eight years ago, there hasn’t been anything.

“This area is semi-arid and potable water is a problem and we had promises that our water situation will be rectified, but that has just been talk. Our women are travelling distances to get water. And soon these gullies will dry up and our cattle with also have problems with water. So in short, we have not seen or had the advantages of having diamonds being mined from our area. We have benefitted nothing.”

—

The life of a ‘gweja’

It is as much a waiting game as it is one of life and death.

They sit at a shopping centre near the diamond fields of Marange in Manicaland province. Eyes cast furtive glances around, senses heightened in anticipation of a good deal.

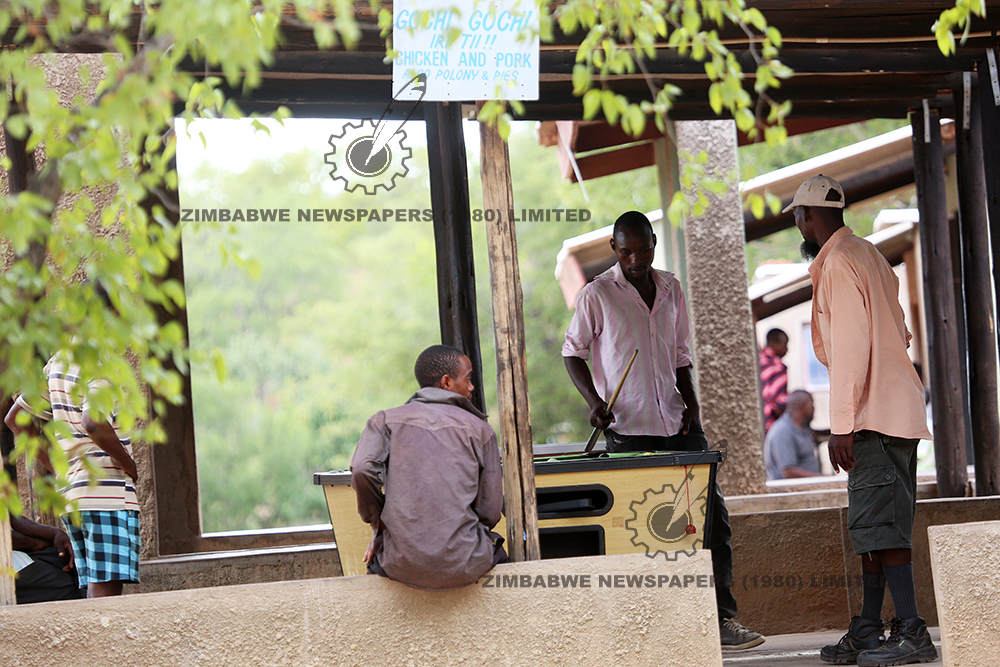

Left: A team of illegal miners find their way into the Mbada Diamond Fields while others spend the better part of the day playing pool. The majority of the youths in and around the Chiadzwa mining area have resorted to illegal panning

Left: A team of illegal miners find their way into the Mbada Diamond Fields while others spend the better part of the day playing pool. The majority of the youths in and around the Chiadzwa mining area have resorted to illegal panning

These hardmen, commonly known as “magweja” in illegal diamond dealing circles, keep a keen interest in everything going on around them.

Every new face presents either an opportunity to make some money, or get thrown in jail. Every arrival is approached warily: this could be a diamond buyer or a security agent.

Knowing who is around them and what is going on is a matter of utmost importance to magweja.

The intel is their lifeblood, helping them evade arrest and make earn dollars.

Law enforcers have been doing the rounds more and more in recent weeks as a new diamond rush threatened to create chaos in Marange’s Chiadzwa area.

New settlers . . . Livestock roam freely in the once secure mine fields exposing this heavy mining equipment to damages.

An unsuspecting individual is easily fooled into thinking the men milling around Tenda Shopping Centre are only interested in the wise waters. But this actually a diamond trading centre of sorts.

People exchange “intel” on security crack downs, which areas are producing good results for panners, which buyer is offering the best prices and so on.

The gwejas operations are systematically divided into day and night shifts.

The companies have left a trail of destruction due to mining activities

The companies have left a trail of destruction due to mining activities

The day operation, which takes place under the scorching sun, is commonly known in the area as “live-wire missions”. This shift is the most preferred by those outside the dare-devil bracket.

How so?

According to the gwejas, police operations are not as tight during the day as at night because of the sizzling sun.

Then there is the night operation, which is said to be the most sophisticated and hazardous. It involves the use of torches, candles and – disturbingly – rogue low level State and diamond companies’ officials.

“It’s more difficult to operate at night hence the panners end up enlisting the services of rogue officers operating in the mine fields for protection. This way they are guaranteed of safe ventures,” said a Government official who spoke anonymously.

It is not out of the ordinary to see young males, some in their early teens, breaking barricades and sprinting at full-throttle with rubble-filled 50kg sacks on their back in the searing weather. They then sift through this ore in search of the famed “ngoda”.

And after risking life and limb, many of these panners squander their illegally acquired gains on booze and sex.

Like panners in other parts of the country, the gwejas’ lifestyles are extravagant.

Possibly this explains why the area that is characterised by pitiable homesteads surrounded by makeshift lodges used for trysts.

Commercial sex workers frequent the area, and they make use of the “lodges”, which do not belong to locals but to “foreign investors” that come in to get their piece of the pie.

The Marange community would definitely be a better place if the devious minds plundering the diamond fields invested in proper housing.

Headman Hondo Mukwada says, “I think Marange is the poorest area in the country despite the rich minerals we have. Our wish is to just have decent, not best, housing and social amenities in the area. Unfortunately we just have pits and bad roads as part of legacy.”

—

The Debswana Diamond Example

Debswana Diamond Company Ltd, or simply Debswana, is a mining company located in Botswana, and is the world’s leading producer of diamonds by value. Debswana is a joint venture between the government of Botswana and the South African diamond company De Beers; each party owns 50 percent of the company. Debswana operates four diamond mines in central Botswana, as well as a coal.

Headman Mukwada

Debswana was formed as the De Beers Botswana Mining Company on June 23, 1969, after De Beers geologists identified diamond-bearing deposits at Orapa in the 1960s. Over the next five years, the government of Botswana increased its ownership stake from an original 15 percent to a full 50 percent.

On March 25, 1992, the name of the company was changed to Debswana Diamond Company (Proprietary) Ltd. The company’s primary objective is diamond mining and associated processes. Debswana operates the Orapa, Letlhakane, Jwaneng and Damtshaa Mines.

The four mines have contributed significantly to Botswana’s socio-economic growth through diamond revenue, transforming the country from an agriculturally based economy in the 1960s to a country that has consistently displayed one of the highest economic growth rates in the world.

All diamond mining in Botswana is controlled by Debswana; there are no private diamond mining operations in the country.

Combined production of the company’s four mines totalled 30 million carats (6 000kg), nearly a quarter of the world’s annual production of around 130 million carats (26 000kg).

The high value per weight of diamonds mined by Debswana has made the company the leading producer of diamonds by value in the world. Debswana is also the second largest producer by volume. Russian diamond mining company Alrosa is the world’s diamond producer by volume.

Villagers and school children still have to walk for long distances to get to schools and clinics in the area on the potholes-ridden dirty roads

Villagers and school children still have to walk for long distances to get to schools and clinics in the area on the potholes-ridden dirty roads

Villagers and school children still have to walk for long distances to get to schools and clinics in the area on the potholes-ridden dirty roads

Diamond mining activities have fuelled much of the growth in Botswana’s economy, allowing it to grow from one of the poorest countries in the world when it became independent in 1966 to a “middle income” nation, with $9 200 per capita income in 2004. Largely because of this, Botswana is considered by two major investment services to be the safest credit risk in Africa. Diamonds account for fully one third of the nation’s GDP, over 90 percent of earnings from exports, and 50 percent of government revenues. Debswana is the largest non-government employer in the country, employing approximately 6 300 people, of whom over 93 percent are Batswana.

Debswana is also the largest earner of foreign currency. – Online