The Sunday Mail

Chris Chenga Open Economy

The pre-eminent interpretation of volatility in common speech is one of the frequent variations in returns and profitability. It is often phrased as “the market is volatile”. Many markets across the globe today are reflecting increased volatility for investors. Typically, financial investors are conditioned to reference high level macro-economic metrics as sufficient explanation of this volatility.

For instance, financial analysts tend to reference slower growth in a trade partner, falling or rising commodity prices and central bank monetary policies, to mention a few metrics. Quite often, political stability finds mention somewhere in there.

We are living in a highly financialised age of capitalism. Arguably, finance has never been more prominent. As such, how financial investors interpret economies and verse their understanding is increasingly influencing policy-makers as well.

Policy-makers with the sincere intention of competitively attracting capital into their respective economies have upped their efforts to satisfying these financial investors. Unfortunately, the same shortcomings found in a financialised interpretation of economies are then transferred onto policy-makers.

By merely focusing on high level macro-economic metrics, financial investors lack adequate investigation into the societal dynamics that could more accurately explain the volatility occurring in most markets.

This sequence means that policy-makers are vulnerable to the deficiency of undervaluing the grassroot societal dynamics of their constituents at the expense of consultation from high level macro-economic focused investors.

Consider the recent Brexit referendum. Indeed, the majority of observers who pay attention to societal dynamics should not have been surprised by the winning Leave vote. Discontent and anxiety have been brewing across many communities within the European Union.

It would not be far-fetched to assume that financial investors who lost money in the volatility after the referendum had completely missed this societal reality as the different outlook offered by a high level macro-economic analysis made a Stay vote rational expectation.

Much more condemning of financialised analysis, the disparity of awareness is reaffirmed by the dismissive “populist” branding of Leave voters. Popular societal will should hardly be brushed off as populism, especially by anybody paying adequate attention to grassroots societal interactions.

My intention is not to advance a diatribe against financial investors; rather it is to highlight the increasing disparity between what financialised capitalism perceives to be contributing to economies, and the societal realities that are actually taking place in these volatile economies.

Europe has served as an example for all of us. Policy-makers should take heed! They can learn from economists who until recently were captivated by the ideology of austerity, which was simply an expedient instrument to appease the vested interests of financial investors.

Africa is increasingly warming up to the world of sophisticated finance, financialised capitalism. Many countries have already committed to independent central banks and the thought of liberalised capital markets is gaining traction.

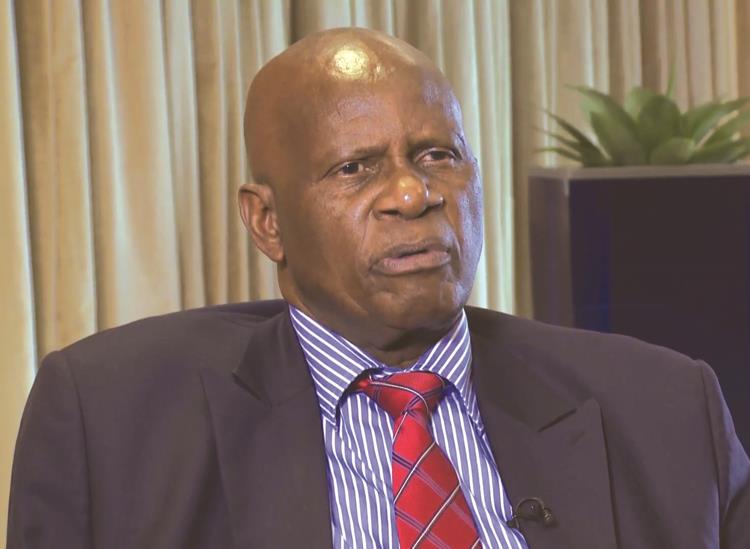

Conventional market agents frequently call for increased flows of FDI. Policy-makers such as Finance Minister Patrick Chinamasa have recently joined the customary trips taken by his continental counterparts to pitch our economies to financial investors in financial hubs such as London.

When Minister Chinamasa and Reserve Bank of Zimbabwe governor Dr John Mangudya travelled to London last week, hopefully they retained the guidance that our economy must be managed along societal clarity.

Finance plays an indisputable role in development and it is unintelligent to proffer that we do not need it. However, as referenced in the aforementioned volatile economies which have had access to finance over the years, capital that is divorced from societal relevance will lack potency.

Perhaps then our policy-makers should commit to drafting strict outlines of the societal conditions that can be improved by financial investment. I will suggest three societal metrics that we attract into our economies. The first two are not very different.

Firstly, policy-makers must emphasise effective allocation. Financial allocation must be intentional from a policy-maker’s perspective. Zimbabwe particularly requires targeted lending to sectors that have a proximity to, and a multiplier effect on specific demographics and societal concerns.

For instance, Minister Chinamasa must be aware of where the majority of the country’s workforce fits in terms of occupational competence and livelihood dependency. Financial flows must be directed towards investments with potent effect on those identified demographics.

For instance, Africa has historically received large sums of capital into the mining sector. However, the societal composition of African economies (dual economy in Zimbabwe) meant that investment into mining never quenched most citizens.

As such, mining has traditionally been a savvy investment portfolio for financial investors, yet it has been separated from directly enhancing the societal concerns of our countries.

In some sort of irony, a Stay vote was widely popular in London, which is a financial hub because the finance sector has offered greater occupational opportunity and prosperous livelihoods than what membership in the European Union has given to other sectors of the British economy.

Allocation of capital has a significant societal influence. Secondly, policy-makers must hold financial investment accountable to equitable distribution. Volatile markets globally are a reflection of the inequitable distribution of capital.

Minister Chinamasa must be cognisant that shrewd distribution of financial investments in a country can actually ease central Government’s fiscal burdens. Indeed, this is a holistic approach that requires consultation with other ministries and depends on central Government disbursements.

A quick example is the notion of zoning investments with the Ministry of Macro-Economic Planning and Investment Promotion. Sustained social harmony in a country is dependent on all provinces, municipalities and central Government’s developmental concern.

This parity is experienced through different regions receiving a fair share of capital allocation and financial attention. Interestingly, a map outline of the Brexit vote showed a clear geographic pattern of Leave vs Stay voters, and this pattern corresponded with disparate levels of economic development.

Likewise, voter sentiment was significantly leveraged on the perception of divided economic attention given by governance to different regions. The last metric of which to measure potent financial investment is sustainability.

As Africa learnt in the last decade, financial investors often trace business cycles and commit only as far as the tide is high. As the commodity supercycle was kind to Africa, financial inflows were in abundance. When the cycle reached a trough, finance pulled out immediately.

As a continent, we lost more than US$50 billion in capital flight last year alone. This investment did not have much to show in terms of its sustainable impact on our economies.

The recent visit to London by our policy-makers led by Minister Chinamasa and Dr Mangudya was good. We are an economy that functions in a financialised global economy.

While we should be wary of the misguided influence that an over-emphasis of financial interests may have, it is our responsibility to capture and utilise that finance with the guidance of societal clarity.