The Sunday Mail

THE truth always has a way of coming out. While Peter Baxter, wrote the book “Selous Scouts: Rhodesian Counter-Insurgency Specialists,” with the hope of painting Rhodesians as victors in the liberation struggle, his narration exposes the ineptness of the Rhodesian forces.

Clearly, the Rhodesian forces had lots of resources to fight against the freedom fighters who in the beginning of the struggle used the “pepesha”, a very basic and simple gun to execute the struggle. However, as is always said, “weapons don’t fight a war.”

Despite their superiority in terms of ammunition, the Rhodesian forces were outsmarted by the freedom fighters.

The following narration by Baxter, which exposes how the notorious Selous Scouts made several attempts to assassinate the late Vice President Joshua Nkomo, is enough to show how the Rhodesian forces were outsmarted by the freedom fighters.

The following is a narration by Baxter. Read on. . .

In the meanwhile, events within Rhodesia reached a nadir when, on 3 September 1978, Air Rhodesia flight 825 was shot down by a surface-to-air missile soon after take off from Kariba. The aircraft crashed into cultivated field, killing 38 of the 56 passengers on board with ten of the survivors being bayoneted and gunned down by a ZIPRA unit that arrived on the scene soon after.

The Rhodesian public was shocked to the core by this event (which indirectly motivated the ‘Green Leader’ raid, or more correctly, Operation Gatling). Global reaction to the outrage was predictably muted, which served only to deepen the sense of isolation felt within the country.

The feeling was magnified even further by ZAPU leader Joshua Nkomo, who responded with an amused chuckle on a BBC interview, admitting that his forces had been responsible for the outrage.

The feeling was magnified even further by ZAPU leader Joshua Nkomo, who responded with an amused chuckle on a BBC interview, admitting that his forces had been responsible for the outrage.

The Rhodesian government had in fact been engaged in a love-hate relationship with the ZAPU leader, dating more or less from after his 1974 release from detention. Nkomo was seen in many quarters as the lesser of a number of political evils, particularly once Robert Mugabe had emerged as the leader of ZANU.

If at least one of these hard-line nationals was needed to authenticate any internal settlement, then rather it be Nkomo than Mugabe. Later, however when Nkomo was proved complicit in the shooting down of flight 825, he had to be viewed with nothing less than vengeful wrath.

What to do about Nkomo in the aftermath was debated passionately at various levels of government. The decision to assassinate him was made, and in his most notable coup so far, the job was given to Reid-Daly and the Selous Scouts to take care of.

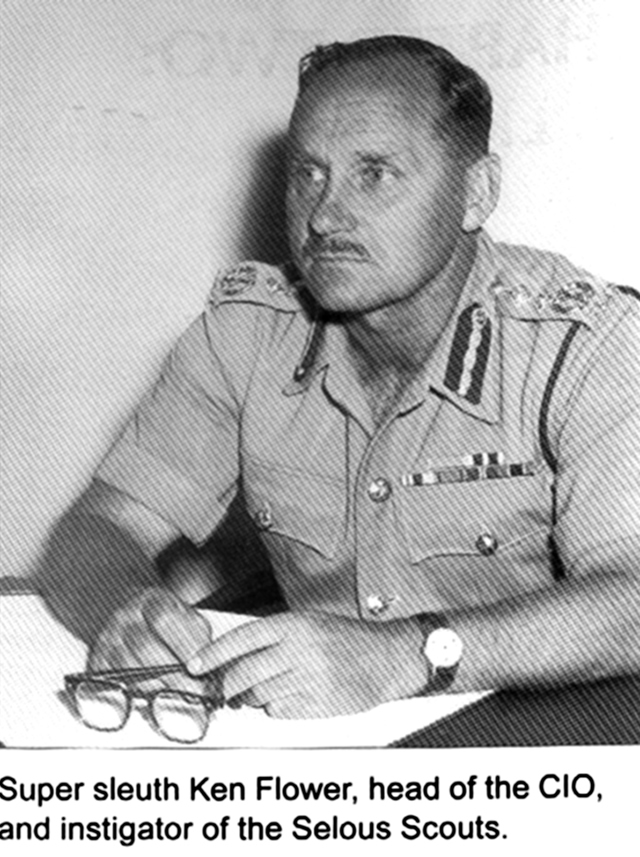

The first dirty puddle that Reid-Daly stepped into was in recognising the fact that somewhere in the system there was a security leak. This fact, in the years since the onset of war, had become more or less established. The British undoubtedly had a mole in the CIO, and Ken Flower’s name, rightly or wrongly, has often been suggested.

That Reid-Daly suspected something like this at the time shows that he was a lot sharper than many people suspected. The fact that he sought to exclude a number of high-ranking military men, some exceeding him in rank, from the ‘need to know; circle, irritated many of them. His relationship with Peter Walls was also in very conspicuous use at this time.

The operator chosen to undertake the mission was Lieutenant Anthony White, a well-seasoned Selous Scout with all the attributed of guile and courage a task such as this would require.

Nkomo was known to be a slippery character and extremely alert to the risk of assassination. A year earlier his deputy, Jason Moyo, had been killed by a parcel bomb; in 1975 ZANU Chairman, Herbert Chitepo, had been obliterated in a car bomb explosion. With the Air Rhodesia atrocity so fresh in the minds of white Rhodesia, an attempt on his life would be almost inevitable. He was also notoriously fond of foreign travel and could be found junketing abroad as often as the ZAPU purse would allow.

It was decided that a radio-detonated car bomb would be the most suitable tool for the job. An appropriate model was located and adapted in the Selous Scout workshops before being transported north via Botswana. White was, in the meanwhile furnished with a finely crafted cover and flown to Zambia from Johannesburg via Kenya, posing as a British taxidermist on the lookout for business opportunities in Zambia.

From the onset, however, the operation was dogged with bad luck. A comprehensive reconnaissance revealed that Nkomo was careful to select random routes and timings in his movements through Lusaka. Seven attempts to preposition the car bomb were thwarted, along with frustrating bouts of inactivity occasioned by Nkomo boarding an aircraft and disappearing for indeterminate periods. White began to run out of money, was anxious that he was beginning to attract attention and in the end opted to abandon the project, destroy the car and follow a pre-prepared extraction deal.

From the onset, however, the operation was dogged with bad luck. A comprehensive reconnaissance revealed that Nkomo was careful to select random routes and timings in his movements through Lusaka. Seven attempts to preposition the car bomb were thwarted, along with frustrating bouts of inactivity occasioned by Nkomo boarding an aircraft and disappearing for indeterminate periods. White began to run out of money, was anxious that he was beginning to attract attention and in the end opted to abandon the project, destroy the car and follow a pre-prepared extraction deal.

Even this was thwarted. He was required to make his way through the countryside to a location that would be under daily air surveillance by Rhodesian aircraft. Unfortunately, after walking some 30 miles through the bush, he began to suffer from symptoms of dysentery, complicated by encountering a native poacher who attempted to apprehend him, suspecting that a reward might accrue should he succeed. He did not succeed.

After a short but vicious brawl the poacher was dead and White was left with no choice but to cautiously make his way back to Lusaka. From there he nervously boarded a scheduled flight and left the country.

Reid-Daly grasped the nettle and briefed ComOps on the failure. He assured the committee that the operation was still viable and was given a second bite of the apple.

This time Reid-Daly decided to augment the undercover-agent principle with something more in keeping with that the Selous Scouts did well. Another operative would be infiltrated into Zambia, but this time purely for the purpose of surveillance. Once it had been established that Nkomo was in residence, the killing blow would be struck by a conventional military assault mounted against his home.

The plan was simple. Surveillance would be kept on Nkomo’s movements to establish his presence in Lusaka, while at the same time a suit ale landing zone would be identified close to the capita; form where an assault team would be helicoptered in for the purpose. The operative chosen for the task was Mike Borlace, an ex-Royal Air Force pilot and one of the more daring of a fearless breed of Rhodesian air force helicopter pilots. Borlace had sought a commission in the Selous Scouts in the hope of “interesting work”, a request now about to be granted.

Interesting, in fact, would be an understatement. Borlace made his way to Zambia while an eight-man Selous Scout assault team led by Lieutenant Richard Passaportis went on standby at Karoi.

A vehicle-a Land Rover, some might say a questionable choice if a reliability is required-was chosen and customized and sent north, but was stopped at the Zambian-Botswanan border and turned around because the driver lacked a visa. A third attempt was made which at last succeeded. Borlace collected the vehicle in Lusaka after cooling his heels for two weeks and began in earnest to lay the foundation of the plan.

And then, to add to this catalogue of petty frustrations, Borlace began to run out of money. He was able to borrow locally but it all served to draw attention to himself, which was not in the least bit helpful. While reconnoitring a possible landing zone he ran into a Zambian military reserve and was detained briefly by a well-intentioned commanding officer who served him tea. Then Joshua Nkomo abruptly left the country, as was his habit, returning to Lusaka a few days later.

Now Nkomo was home, the message was relayed and that evening two laden helicopters took off from a forward airfield in Karoi with the bristling eight-man attack force aboard.

Borlace, however, en route to the pre-arranged rendezvous, ran up against the obstacle of two washed-away bridges thanks to heavy seasonal rain and was unable to keep the appointment. For their part the Selous Scout assault force was landed in no less trouble. An accidental shooting resulted in the serious injury of one of the members, which required a second operative to stay with him while the remainder of the team pressed on. Their movement was constrained by heavy bush that had grown as was usual in the late season and the steady rain and mud was a backdrop to it all. They arrived at the rendezvous but found it deserted. Shortly after, they and the wounded man were uplifted and returned to Karoi.

Back at Inkomo the plan was rehashed and two days later the Scouts were airborne once again. This time Borlace arrived at the rendezvous on cue but found no sign of the attack team. Passaportis and his mean had become weighed down by wet seasonal conditions and arrived at the site only at first light. There, to their horror, they discovered that they had blundered right into the midst of a Zambian army exercise. They took cover as a Zambian army patrol came into view and stumbled on their tracks, radioing in immediately for backup. At this the Scouts wisely took to their heels. They managed to stay ahead of their pursuers, eventually outrunning them before being uplifted back to Karoi.

The whole episode began to appear surreal. The blacks said Nkomo had a muti stick that protected him from harm. Most of the white Scouts laughed at this, but there were some who did not. Whatever might be at the root of it, this was a devastating run of bad luck. For Borlace waiting at the ‘sharp end’ it was particularly unnerving. Each day his face became better known and his ongoing money problems were increasingly drawing attention to him as any one of a million possible scenarios of capture began to plague his mind.

Meanwhile, the plan was again rehashed and simplified; the strategy was now to parachute onto a golf course adjacent to Nkomo’s house, staging the attack and then navigating out of Lusaka on foot for a pre-planned rendezvous for a helicopter uplift.

Time, however, had run out. The attack force set off in the belly of a C-47 Dakota transporter ready to leap out over the metropolis and assassinate the ZAPU leader. Over Lusaka, however, there was no sign of Borlace. The mission aborted and returned to Rhodesia.

In the meanwhile, something had taken place that had convinced Borlace that it was time to leave. Reid-Daly received word form a fellow passenger on a scheduled flight that Borlace had been called in and detained by Zambian officials. A few days later the grim truth was confirmed: Borlace was in a Lusaka prison and could expect things to get very unpleasant, as indeed they did.

Reid-Daly and the rest of the Rhodesian high command were consternated. The Rhodesian security community was small, as was the Selous Scouts itself, and such things did not happen without it affecting the entire service. For Reid-Daly it was particularly bitter.

His subsequent exchanges with ComOps and General Walls have never been recorded, but it is likely he was kept very busy putting out fires, as one attempt after another to free Borlace was aborted. This time, however, he was ordered to lend Lieutenant Anthony White to the Supers because the SAS had been given the job.

Not least, it was the wounded pride that stung the heart of both the commanding officer at the Selous Scouts and his regiment, aggravated by crippling antipathy that had been generated against the unit over the last five hard-fought and glorious years of war.

Reid-Daly lobbied hard and gallantly for a reversal of this decision for clearly in his mind was a desire to get to Lusaka by one means or another in order to break Borlace out of prison. He pleaded with Walls the wholly impractical suggestion that the Scouts just fly in and he damned, do the job and get Mike Borlace put of there! Walls refused. Borlace, he said, had now to be considered as a casualty of war.

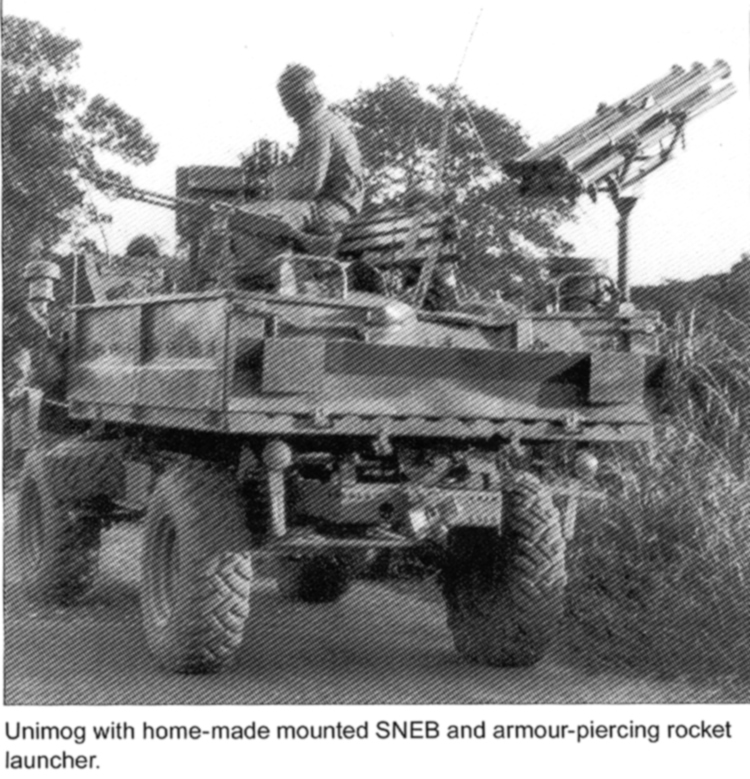

There was nothing that could be done but sit back and see how the Supers handled it. Theirs was a stylish scheme to land several Sabre Land Rovers on the Zambian side and drive to Lusaka, stage a strike against Nkomo’s home and drive home. This they did with a high degree of precision. Nkomo’s house was more or less demolished and a large number of ZIPRA personnel killed but Nkomo himself escaped.

This episode was one of the more intriguing of the more enigmas of the war. Nkomo claimed that he had been in the house but had escaped through a toilet window. Analysts, which everybody in Rhodesia was at that time, dismissed the suggestion.

The notion that the lumbering Nkomo, morbidly obese and barely capable of unassisted movement, might squeeze himself out of a toilet window in the midst of a ferocious firefight beggared belief. In all likelihood Nkomo had not been home, but claimed a narrow escape in order to increase the dramatic effect.

Now that we know what the freedom fighters were up against, next week your favourite Question and Answer Chronicles with the war veterans return to the pages of your favourite newspaper, The Sunday Mail.